Frederick Place

Lead Researcher - Ian Walden

1. Introduction

Frederick Place has a forgotten air about it. Running parallel to Queens Road, the latter’s growth into a major Brighton thoroughfare has coincided with the gradual diminution in significance of its shorter (and topographically lower) neighbour.

Part of the grid system of streets constructed on the ‘North Laine’ (one of five ‘laines’, or open fields, which once surrounded the fishing village of Brighthelmstone), Frederick Place runs from its junction near the station with Trafalgar Street to the North, to Gloucester Road in the South.

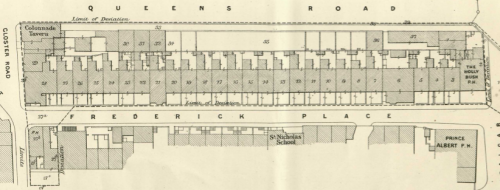

London, Brighton & South Coast Railway plan (detail), 18751

Never an upmarket neighbourhood, the street was originally lined on both sides with houses, many of which were occupied by multiple families. A glance at the street today reveals only a few domestic residences. Virtually all the original buildings have disappeared, with the entire western side of the street now dominated by the service entrances and rear windows of tall hotels and office buildings fronting Queens Road. The sole survivors of Frederick Place’s populous Victorian heyday are the cottages now numbered 29 & 30, and the old school building halfway along the eastern side. Obscured, however, are the multiple, now forgotten, stages between these two extremes, between the street’s construction in the 1840s and today.

2. Development

The original layout of Frederick Place was characterised by residential building, with houses of two or three storeys on both sides. Those on the West had relatively long rear yards, and small front yards as well. One notable change from today is the original presence of Frederick Cottages, a row of tiny cottages running East from Frederick Place and accessed by a small flight of steps down from street level.

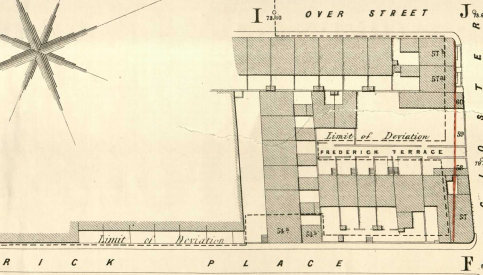

Brighton Improvement Bill 1859 (Queen's Road widening) plans

(detail, with Frederick Cottages in centre, perpendicular to Frederick Place)2

The construction of the railway and the arrival of London trains at the terminus station from 1841 soon led to calls for the widening of Queens Road as the main route from the station to the seafront, with the Brighton Improvement Bill passed in 1859. However, this was slow to affect the West side of Frederick Place, taking real hold during the 1870s and 1880s. In 1865, the long rear gardens of those houses were still intact.3 However, with Queens Road already being some 30 feet higher than Frederick Place, and with property being developed, this would cast a deep, permanent shade on those properties, and associated problems of waste water drainage, etc. While the 1871 census had a full list of occupants for nos. 1-29, which comprised the West side of the street, these had all vanished by 1881.

Frederick Place, Brighton, by William Thomas Quatermain

(shows no. 8 from the perspective of Frederick Cottages; 1870s).4

Compare with the photograph of Frederick Cottages below, taken from the same spot in 1935

Building plans for the construction of a bacon drying house in 1888 illustrate the new kinds of building, less dependent on daylight, now occupying the street.5

It is only in the late 20th century, however, that these sites have been taken over as rear extensions of Queens Road businesses. Trade directories up to at least 1961 show a number of warehouses and other commercial ventures opening onto Frederick Place itself.

The 1870s saw change elsewhere in the street, with the considerable widening of Gloucester Road itself, including its junction with Frederick Place. Coming in 1878, this necessitated the demolition of the ‘Army and Navy’ Beerhouse on the South-East corner of Frederick Place, and subsequently enabled the passage of much larger vehicles into and out of the road.6

Plan of 1878 road widening

(property coloured blue surrendered to the Corporation and demolished)7

Demolition of houses on the East side came later. Trafalgar Cottages were condemned as ‘slums’ and demolished in 1936. They would later be replaced by the new Gordon House (see ‘Trade’, below).

Frederick Cottages, just prior to demolition, 19358

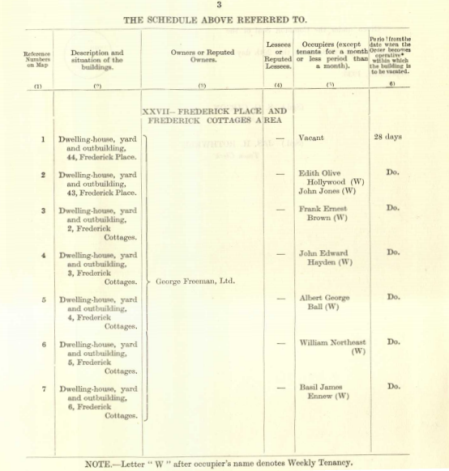

Slum Clearance Area plan - Frederick Place & Frederick Cottages9

The larger properties at nos. 36-41 (the East side, south of the school) slowly decayed through the later 20th century. They were replaced by the present office building, Frederick House, by May 1987.

36-41 Frederick Place, looking North, 4 June 196110

Frederick House, 13 May 198711

The new houses to the north of the school, set back from the road, date from between 1987 and November 1990.12 They replaced a pair of houses then numbered 33-34, demolished in 1960, and the commercial premises long occupied by Pickfords, the removal and carrier company.

3. Architecture & Materials

As described above, the street as it now stands is dominated by 1980s and 1990s concrete and brick construction. Earlier properties include the cottages numbered 29 & 30. Their architectural style - flat frontages and parapeted roofs - is in the late Regency tradition and indicates a date of the early to mid 1840s at the latest. Late 1840s buildings typically incorporate canted bay windows rather than flat ones, and external cast iron gutters rather than ones hidden behind parapets.

Nos. 29-30 in September 2017 (Image courtesy of Google Streetview)

Located behind the Prince Albert pub on Trafalgar Street, they originally formed one end of a terrace that reached to the school building (with a passage between nos. 31 and 32, giving access to a yard behind, surrounded by stables and small store houses). The building line of this terrace is visible in the paving, and delineates the modern parking areas of the new terraced housing to the left. On the gable end wall of the ‘Old School House’ there is a ‘ghost’ imprint in the fabric, where the roof of the (demolished) original terrace was keyed into the school when the latter was built.

Interestingly, no. 28, now little more than a garage, was once a stable belonging to the pub, converted in 1888 into a small cottage in its own right.13

Although a school existed on the present site from around 1855, the present structure, now known as the ‘Old School House’, belongs stylistically to the late 19th or early 20th century. The projecting front gable wall, with its slightly ‘Gothic’ inset arched head to the first floor window, is typical of the period. Note how the front elevation was set back from the building line of the surrounding terraces, to allow for the construction of a half-basement.

The Old School in September 2017 (Image courtesy of Google Streetview)

Turning around, we should also consider the matching pair of industrial buildings, one plain sandy brick, the other with white rendering, on the West side of the street.

Rear of no. 83 Queens Road in September 2017 (Image courtesy of Google Streetview)

Now office buildings, occupied at the time of writing by PSE Associates, Quantity Surveyors, this tall brick structure forms the rear of no. 83 Queens Road. Likely dating to the early 20th century, the relieving arch above the main cart entrance has been picked out in brick to be visible, rather than internal and hidden; a very typical device from the Edwardian period right through to the 1920s. It is also interesting that the brick building retains a hint of ‘classical symmetry’ - the string courses between each floor and the pilasters tend to unify the appearance of the twin building. These classical elements conferred visual ‘status’ which was clearly important here, as it was with a majority of late Victorian and Edwardian industrial buildings. To enable the heavy loadings of industrial machinery within such high and narrow buildings the outer walls would have needed to be particularly strong. As with the relieving arch mentioned above, the pilasters are a visual interpretation of the internal structure.

4. Ownership Patterns

While we have no deeds for the original housing, it is highly likely that all the original occupants were tenants; this is certainly true of those occupying the properties identified in the 1930s slum clearance orders, who were on weekly tenancies, paying in cash.

List of properties to be demolished and residents to be re-housed14

The deeds we do possess are all for the later business premises, which appear to be mainly owner-occupied or on long leases. These include the Army and Navy Beerhouse, sold by owner George Freeman to the Brighton Corporation for demolition prior to the 1878 widening,15 and the bonded warehouse on the West side of the street, long owned by the Reeves family, although some parts were leased.16

5. Notable Buildings

As we noted above, St Nicholas School existed on its present site from 1855. A Draft Deed of Trust dated 13 June of that year describes the building as occupying much the same plot as today - 37’ x 90’, bordered on the West by Frederick Place, and on the East by the rear yards of Over Street.17 The school expenses account book opens in July 1855, listing items for ‘cleaning school’, which implies the recent completion of construction.18 However, we see that the current building is from a later date, although sadly no alteration plans can now be found.

St Nicholas Memorial School, 193819

With the closure of the school in 1944, and the building’s sale in 1958, its use changed. The industrial lifting device seen above the window in the photo below presumably dates from its time as a ‘joinery works’ operated by Gates & Son.20 Its subsequent occupants include a shoe wholesaler, and a more recent conversion to flats.

Frederick Place, looking South, 27 November 199021

Two other buildings once occupied the southern end of Frederick Place, and both would have stood out as notable architectural landmarks of the street in their time.

The first, fronting Queens Road, was the impressive ‘Colonnade Hotel’. Frederick Place housed the service entrance and the ‘Shades’ bar of this ornate, 35-bedroom, turreted creation of the late 1870s.

Colonnade Hotel plans, 12 October 1877 (Queen's Road elevation)22

Colonnade Hotel (Frederick Place elevation - much plainer than the front!)

Source reference as above

Colonnade Hotel plans, 12 October 1877

(basement, showing Shades bar in upper right corner)

Source reference as above

The second was the combination of house, shop space, warehousing and offices belonging to George Freeman, proprietor of a significant firm of builders’ merchants. This site was reduced by the widening of Gloucester Road in 1878, and finally replaced by the Frederick House development in the late 1980s. In their time, however, these structures would have been visible high above the rooflines of the surrounding terraced housing (for images, see ‘Trade’, below). By 1897, Freeman’s business was sufficiently successful that an impressive office building could be constructed on the corner plot.23

Freeman also owned all of Frederick Cottages plus nos. 43-44 Frederick Place, and the building seen in the far right of the picture below, dated 1968, replaced these structures. This dates it between their demolition in September 1936 and 1968.

37-41 Frederick Place, and George Freeman Ltd, 10 June 196824

6. Residents

Judging from census data, most residents of Frederick Place between 1841 and 1911 were short-term occupants, appearing in no more than two consecutive returns. Many would aspire to move out to more spacious accommodation, not shared with other families. Some would move on in search of work, while no doubt others could not keep up rent payments and slid further down the social scale, to the infamous poverty of Orange Row or the ‘Pimlico’ area.

Some long-dwelling exceptions can be found, however. William Oxford, a plasterer born in Portsmouth around 1790, was listed living in Frederick Place by 1841, with his Sussex-born wife Sarah and their four daughters, aged between 7 and 15. The daughters grew up and left home, and by 1851, only the youngest, Jane, was still at home. Another decade on, and Jane had left - but her eldest sister, Ellen, had been married and widowed, and moved back in with her parents, now with her own young daughter. These four shared no. 3 with two other couples, the Phillips (in their 60s) and the Whittings (with two young children of their own). The last we see of William is in the 1871 census, aged 81, widowed, and with only an unmarried brother and sister in their 50s living at the same address, presumably his lodgers.

Harriet Banbury lived during the same period at no. 14, also on the now-rebuilt West side of the street, advertising her services as a laundress in the local trade directories for 30 years. In 1961 we see her sharing the house with her daughter, son-in-law and grandchildren, and a young girl in service, from Forest Row.

Henry Cozens, a local Brighton blacksmith, and his wife Elizabeth raised five children at no. 22, already being resident before the railway in 1841, and having sole occupation of the house. As the years pass we see their children marry, and enter skilled professions (dress making, millinery, cookery, and the youngest son William follow his father into the smithy). In 1871 we see Henry, now bereaved, but with two daughters, his son-in-law, and a granddaughter around him.

Entering the 20th century, we can follow the career of George Swaysland, advertising his hairdressing business at no. 29 Frederick Place in local trade directories. Aged 40 in the 1911 census, and living alone, he appears finally in the Kelly’s directory for 1939 - but a Mrs. Swaysland was still listed there as late as 1951.

A sadder note concerns one of the few coroner’s records relating to the street. Although he would not have recognised Frederick Place as his address, Joseph Todd ended his life here in the early hours of Friday 4th December, 1925, by hurling himself from the veranda of his Queens Road flat. This verandah can still be seen today from Frederick Place; it is the left-hand of the two older brick structures on the West side of the street (in 2017 it was rendered in white, and occupied by PSE Associates).25

7. Life & Work

Census returns from 1841 to 1911 demonstrate that Frederick Place was a crowded place to live. Compared to the ten or twenty occupants we would expect from the present-day housing stock, we see 263 residents in 1841, rising to a peak of 339 people in 1861. The houses were larger than in some of the nearby North Laine streets, but that still represents an average of over eight people per household, typically with two or three families sharing. Most households by the late 19th century also included a lodger or two (typically male), or a teenage girl in service (often from outside Brighton; perhaps a cousin or friend’s daughter).

By 1881 the Western side of the street had ceased to include houses, and we see the total population drop off to 132, continuing to fall into the 20th century. In 1911 only 85 people lived here, spread among fifteen addresses. Not only had the housing stock been reduced, but households were smaller, averaging between five and six people per household.

What work did all these people do? We see a variety of occupations listed. In the street’s early years, we see a high proportion of servants. Some would be in private houses, but others would be maids, cleaners, waiters, or bar staff in Brighton’s growing range of hotels, pubs, and restaurants. After the railway’s arrival, we see a growing number of people engaged in manual trades. Some are directly related to the railway, such as porters and engine fitters. Others powered a growing town, such as bricklayers, cordwainers, dyers, carpenters, and painters. With the arrival of warehouses in the street (and many more nearby), the need for carters and stable men grew. As the turn of the century approaches, an increasing number of white-collar jobs appear. Before computers and photocopiers, all businesses needed an army of clerks to keep functioning, and Frederick Place was home to such men working for merchants, printers, publishers, and other local enterprises.

Most women, in addition to the work of bringing up children, cleaning, shopping, and cooking, also needed to produce income in order to make ends meet. Throughout the 19th century, at least six Frederick Place women at any one time were advertising themselves as laundresses or dressmakers. Occasionally a widow might keep up the rent by turning lodging-house keeper, as Sarah Upfold was doing at no. 7 in 1851.

One slightly unusual occupation for the time was that of pub landlady. We see two women as mistresses of the Colonnade Shades at no. 1 (the South-West corner of the street). Initially a side-business for the Bollen family of coopers, this was made a full part of the Colonnade Hotel by 1851 and was managed by Jane Baker, from Hammersmith. Another Middlesex woman, Elizabeth Edwards, had taken over by the publication of Folthorp’s 1861 directory, and was still running the business in the 1871 census.

Education: St Nicholas Memorial School

The school is named, of course, after the parish church of Brighton. The ‘Memorial’ part of its name refers, not to the Wellington memorial at the church, as has been claimed elsewhere, but to the circumstances of the school’s founding in 1851. It seems Mrs Anna Cuyler Rose was in possession of funds intended for a girl she saw as a daughter (it is unclear if the girl had been formally adopted or not). When this girl died, she gave these funds in memoriam for the foundation of a school for girls “in some destitute part of Brighton.”26

Being a loyal parishioner, she approached the church, and both Henry Wagner, the vicar of Brighton, and his curate, CE Douglass, took an active interest in the project. Douglass’ 1895 book of prayers for the school notes that this was to be a private foundation, not a parochial school per se, and that although the vicar was always intended to be one of the school’s managers, his relation to the school was to be like that "any private family in his Parish, which attends his Church and in which he takes a religious interest."27

Douglass records that the first step, upon receiving the vicar’s approval and consent, was for him to lease a house in Gloucester Lane (later Road), with space for fifty children. It opened on Tuesday 13th May 1851, at a weekly charge of 3d per child.28

By 1854 Mrs Rose was in a position to give a plot of land in Frederick Place to one Cornelius Cuyler Philip Mair (presumably a brother or close male relative), who we assume organised the construction of the school building (with money donated by a Julia Frances Syms, a contribution recorded on her death in 1906).29 By June 1855 all was complete; to the land and building Mair added an endowment of shares in the East India and Madras Railway Companies, the interest from which would provide the school’s income. The deed of trust establishing the school specified it would be “for the religious instruction and the education of girls of poor parents” between 5 and 13 years of age, with the intention of maintaining an average of 120 daily attendants.30 These children were split, at least in 1889, between five classes. They progressed through the nationally-recognised seven 'standards', with the top class containing older children in several different standards, taught together.31

Below the trustees would sit a board of managers, mostly local clergy, with a treasurer usually taken from the firm of Messrs Howlett & Clarke, solicitors. Day-to-day authority rested with the chaplain (Douglass, the parish curate, would fill this role until his death in 1905), and a lady superintendent (initially Mrs Rose; this post would be abandoned in 1905).32 They would appoint the school mistress, caretakers, assistants, and any ‘pupil teachers’, and would take an active role in visiting the school and assessing the students’ progress.33 The chaplain’s annual report would be the most prominent feature of the annual meetings of the board of managers.34

The School Mistress was of course the face of the school to the local community. She lived on site, with two rooms given rent free, making her a well-known neighbour to everyone in Frederick Place.35 Usefully for our purposes, she also kept a weekly log of lessons taught, assessments, and events in the school. Initially there was quite a high turnover of mistresses, with some getting married, others getting jobs elsewhere, and one dying on the job. The most notable exception was Laura Rawe, mistress from 1884 to her untimely death (in her early forties) in 1903. The log books record her funeral on 9 January of that year, noting that "many dear friends attended and the testimonials were numerous, indicating the universal respect and love in which Miss Rawe was held." In her time she would have encouraged and mentored dozens of young girls as certified ‘pupil teachers’, a paid role usually teaching the youngest classes, requiring assessments and potentially a platform to a full-fledged teaching career (St Nicholas’ mistress in the 1860s, Lucy Norton, came up through this route in her native Northampton). Many of these girls grew up in the school and were from Frederick Place or the surrounding streets. Examples in 1861 include 21-year-old Harriet Russell, a schoolmistress’ daughter living at no. 13, and 16-year-old Emma Leurie, the carpenter’s daughter next door to the school, at no. 34.36

St Nicholas’ School was always a modest size, as the building suggests. The school’s log books and annual reports record, week by week, the school’s average attendance. From those initial fifty pupils, numbers rose once the new building was constructed; by 1856 they varied between 87 and 121, rising to 125 by the mid 1860s, out of almost 200 names on the school’s books. This discrepancy (between enrollment and attendance) is a constant feature; at any one time there was a significant proportion of enrolled pupils who were sick, working, involved in other activities (one entry in June 1890 notes Sunday School festivals as a cause for absence), or whose parents couldn’t afford the modest fees that week. Over the next thirty years, pupil numbers dropped steadily (down to 50 in the winter of 1904-5, as illness took its toll), and with it the school’s income. The disappearance of housing stock from Frederick Place must have played some role, although the increased government funding towards national schools and formal parochial schools, and away from independent charity schools like St Nicholas, must have played a role as well.

Douglass’ report as chaplain for November 1903 makes it clear that he had been hanging on in his post despite advancing age and infirmity. He had been with the school since its inception fifty years earlier, and was waiving his chaplain’s salary, making up for shortfalls in other sources of funding. He knew, however, that any new chaplain would need to take his salary, and that such a transition should be delayed until funding could be obtained. Eventually Canon Bond, the new vicar, accepted the chaplaincy in 1905, taking his salary, but promising to raise an equal amount in subscriptions from parishioners.

At this time a series of small measures illustrate the school’s decline. The teachers unanimously petitioned for the associated Sunday School (apparently Douglass’ private project, with only one or two students) to cease, and for them to get Sundays off. This petition was rejected out of hand, given the ‘Church School’ nature of the institution! In 1905 the post of Lady Superintendent was abolished, and day-to-day care of the school placed in the managers’ hands. By 1909 teachers’ salaries had been reduced, and the School Pence was doubled to 6d per week, but this led only to a further fall in numbers, to an average attendance around fifty, year-round. Although those figures recovered slightly, the impact of war and depression, and increasing government control of education, cannot have helped the school to flourish.37 According to Peter Guy, the school remarkably clung on until 1944, and the building continued to be used as a Youth Club venue until around 1958.38

The School building in Spring 1957 (note the 'for sale' sign)39

Front view of school building in Spring 1957 (same source as above)

8. Trade

We have already noted the predominantly domestic nature of the street, and the occupations which some residents, especially women, were able to pursue from home. In addition to these, the most notable trades in the mid-19th century were the street’s public houses, one on each corner. At the North-West corner, by the railway station, was the Holly Bush. Opposite, still standing, was the Prince Albert. In the South-East corner, later demolished to accommodate the widening of Gloucester Road, was the Army & Navy. Opposite that was the Colonnade Shades, a kind of basement bar for the larger Colonnade Hotel, with its main entrance on Queen’s Road.

Brighton Street Directories such as Page’s, Towner’s, and Pike’s reveal the development of wholesalers, warehouses, and stabling as the century progressed. Long-term traders included EJ Reeves, a wholesale grocer, who operated a bonded warehouse on the street’s West side between 1891 and 1939, and Pickford’s, still a national removal business today, who owned stables and warehouses behind nos. 32-34 between 1888 and 1931.40

By far the longest trading resident of the street, George Freeman Ltd owned the corner plot with Gloucester Road (known as ‘Gordon House’) by 1868. Initially a cement merchant that grew into a more general builders’ merchant, their warehouses dominated the South-Eastern side of Frederick Place. As we saw above (under ‘Notable Buildings’), a shop-front bearing their name remained visible in a photo dated 1968; a full century on a single site.

Plans for Freeman's house and shop, 186841

Planned new warehouse on the same site, 187242

By the second half of the 20th century, newer businesses in the motor and electrical trades began to move into the street, alongside storage-intensive fields such as antiques (see photo below). It is largely these same buildings that characterise the street in the early 21st century, now occupied by offices and service providers, rather than industrial or retail operations.

Frederick Place, looking North, 11 January 197343

9. Conclusion

It is hard not to feel a little sad at the state of Frederick Place today. It is not so much the change of use from residential to commercial space. That reflects the desire, and increasing ability, of working families to find housing that is spacious, healthy, and with access to green space (plus the rising cost of city-centre rents). It is, rather, the loss of a human face that is to be regretted. It is now hard to tell what kind of business is conducted behind those comfortable, bland facades. Their buildings are designed to be neutral, easily exchanged between tenants, with no expression of a business’ history, purpose, or character.

If nothing else, however, the history of Frederick Place illustrates that urban spaces are scenes of constant change, and that the present view is likely to be every bit as replaceable as all the fields, faces, and fortunes that preceded it.

References

1. Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, ref. Q/4/P/413A

2. Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, ref. Q/4/P/288A

3. Building alteration plans: Additions to no. 23 Frederick Place (28 May 1865), East Sussex Record Office, ref. DB/D/8/399

4. Image courtesy of Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove (Digital Media Bank ID 64888; Accession no. fa101776)

5. Building plans: new bacon-drying house for Messrs. Heald & Co. (14 June 1888), East Sussex Record Office, ref. DB/D/7/2534

6. See the Deed of Dedication (of land fronting the Army & Navy Beerhouse) from George Freeman to the Corporation (20 February 1878), East Sussex Record Office, ref. R/C/4/368

7. Ibid.

8. Image courtesy of the Regency Society, available online at http://regencysociety-jamesgray.com/volume25/source/jg_25_182.html (accessed 21 March 2018)

9. Brighton (Frederick Place and Frederick Cottages) Housing Confirmation Order 1936. Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, ref. ACC7600/46

10. Photographs taken as part of the North Laine Enhancement Study (relating to the establishment of the North Laine Conservation Area). Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, refs. BH/H/20/19 and BH/H/20/23

11. Ibid.

12. This terrace of housing is absent from the photo above, but present in a photo of Frederick Place, looking South, dated 27 November 1990 (ESRO reference as above)

13. Building plans: alteration to Stable for Vallance Catt & Co., 18 August 1880. ESRO ref. DB/D/8/2065a

14. Brighton (Frederick Place and Frederick Cottages) Housing Confirmation Order 1936. Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, ref. ACC7600/46

15. See the Deed of Dedication (of land fronting the Army & Navy Beerhouse) from George Freeman to the Corporation (20 February 1878), East Sussex Record Office, ref. R/C/4/368

16. Agreement for lease dated 24 August 1889, ESRO ref. TAM/3/7/2/11

17. Copy draft conveyances of property for various Brighton parishes, East Sussex Record Office, ref. HOW 33/2

18. St Nicholas School expenses account book, ESRO ref. E/SC/34/3/7

19. Image courtesy of the Regency Society, available online at http://regencysociety-jamesgray.com/volume25/source/jg_25_229.html (accessed 21 March 2018)

20. Kelly's Directory of Brighton, 1961 (available at East Sussex Record Office)

21. Photograph taken as part of the North Laine Enhancement Study (relating to the establishment of the North Laine Conservation Area). Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, refs. BH/H/20/19 and BH/H/20/23

22. Building plans for the new Colonnade Hotel, East Sussex Record Office, ref. DB/D/7/1496

23. Building plans: Alterations & Additions to Gordon House (27 July 1897), East Sussex Record Office, ref. DB/D/7/4570

24. Photograph taken as part of the North Laine Enhancement Study (relating to the establishment of the North Laine Conservation Area). Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, refs. BH/H/20/19 and BH/H/20/23

25. Report of Coroner's inquest into death of Joseph Stevens Todd, East Sussex Record Office, ref. COR/3/2/1925/165

26. Correspondence between CE Douglass and HM Wagner, in the Minute Book of the meetings of the Managers of St Nicholas Memorial School (1851-1913), East Sussex Record Office, ref. ESC 34/1

27. Copy draft conveyances of property for various Brighton parishes, East Sussex Record Office, ref. HOW 33/2

28. Minute Book of the meetings of the Managers of St Nicholas Memorial School (1851-1913), East Sussex Record Office, ref. ESC 34/1

29. School Records, St Nicholas Memorial School (1863-1882), East Sussex Record Office, ref. ESC 34/12

30. Copy draft conveyances of property for various Brighton parishes, East Sussex Record Office, ref. HOW 33/2

31. St Nicholas Memorial School Log Book (1889-1906), East Sussex Record Office, ref. ESC 34/3

32. Minute Book of the meetings of the Managers of St Nicholas Memorial School (1851-1913), East Sussex Record Office, ref. ESC 34/1

33. School Rules and Regulations, contained within a file of draft conveyances of property for various Brighton parishes, East Sussex Record Office, ref. HOW 33/2

34. Minute Book of the meetings of the Managers of St Nicholas Memorial School (1851-1913), East Sussex Record Office, ref. ESC 34/1

35. St Nicholas Memorial School: Managers' Annual Reports (1856-70, 1879-99), East Sussex Record Office, ref. E/SC/34/3/11

36. St Nicholas Memorial School: Log Books (1862-1899), East Sussex Record Office, refs. ESC 34/2 and ESC 34/3

37. Minute Book of the meetings of the Managers of St Nicholas Memorial School (1851-1913), East Sussex Record Office, ref. ESC 34/1

38. Guy, Peter. "St Nicholas, Brighton: The Youth Club." My Brighton & Hove. http://www.mybrightonandhove.org.uk/page_id__11565.aspx (accessed 22 March 2018)

39. Photos enclosed within Minute Book of the meetings of the Managers of St Nicholas Memorial School (1851-1913). Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, ref. ESC 34/1

40. Building plans: rebuild store for Pickford & Co., South Side of Yard, Frederick Place (10 October 1888), East Sussex Record Office, ref. DB/D/8/3082

41. Building plans: house and shop for Mr Freeman (25 Mar 1868), East Sussex Record Office, ref. DB/D/7/711

42. Building plans: new warehouse at 44 Frederick Place (12 Mar 1872), East Sussex Record Office, ref. DB/D/7/1201

43. Photograph taken as part of the North Laine Enhancement Study (relating to the establishment of the North Laine Conservation Area). Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, refs. BH/H/20/19 and BH/H/20/23