Street history - Queen's Gardens

Lead researcher Elaine Fear

Download the Queen's Gardens history as a .pdf (1.8Mb)

Introduction

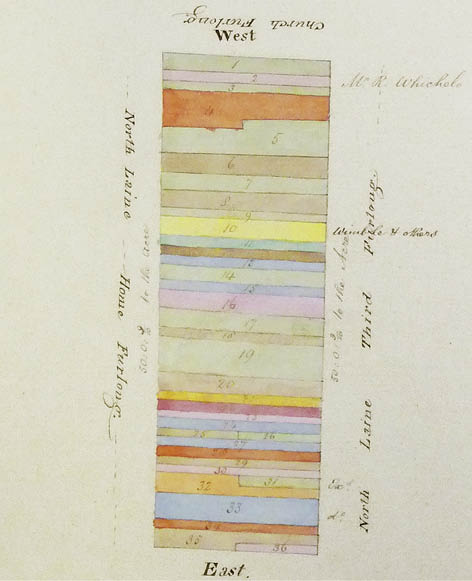

Queen’s Gardens is situated in North Laine, running between Gloucester Lane in the north to North Road in the south. Historically it was part of the second furlong of North Laine in the Common Laines of Brighton.

As with all other land in the North Laine, what was to become Queen’s Gardens had been agricultural land, owned by one of an apparently small group of men. The furlong was divided into strips, farmed by tenants and comprised of market gardens and as such it was part of the activity that supported the growing population of Brighton.

1) Terrier map of Brighton 1792 (Second Furlong here shown framed). Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office. Enlarge

2) Close up of the Second Furlong, 1792. Image courtesy of

East Sussex Record Office

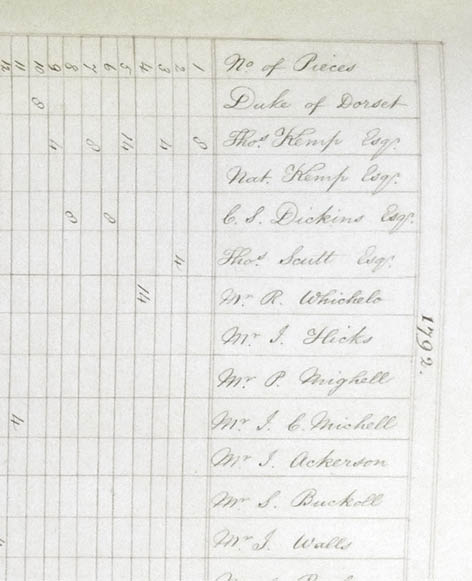

3) Detail from the 1792 Terrier’s apportionment list showing

landholding interests. Image courtesy of East Sussex

Record Office

Development

Each side of Queen’s Gardens appears to have been developed by separate entrepreneurs: the west side, on which numbers 1-16 were built, was owned, at the time of development by William Stevens, but the east side remains more of a mystery. We know this as a result of the different forms of landholding: the west side was copyhold and subject to the Court of the Manor of Brighton for transactions but the east side passed as freehold land, away from the jurisdiction of the Lord of the Manor.1

Scanning the Rolls and seeing the same names cropping up in the land deals of Brighton in the mid-nineteenth century gives a fascinating glimpse of the past. Just as interesting is discerning the way development took place in Queen’s Gardens since this probably mirrors development in other parts of the North Laine. Brighton, already expanded as a seaside resort for the aristocracy and what today might be called ‘celebs’, began to expand even more with the arrival of the railway. The area close to the terminus became prime land for businesses and a target for expansion.

The early Victorian property entrepreneurs would buy and sell land between themselves, and allow builders to erect one or two houses on their land; later these ‘entrepreneurs’ would sell the land to the builders. The builders would then let their property out and also use it as security to raise capital to build further houses. Some of the names involved in this process are still prominent today; Evershed, Dumbrell and Hallett, for example and others reoccur in different generations throughout the century; Attree, Kemp, Catt, Vallance, Scrase and Dickens.

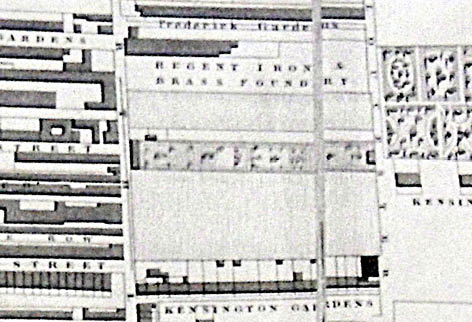

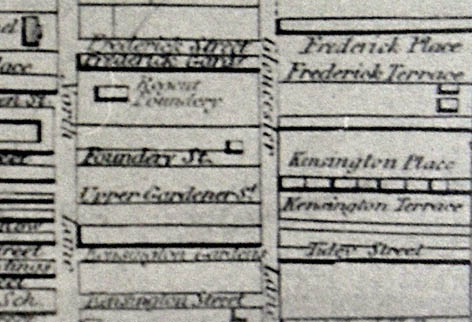

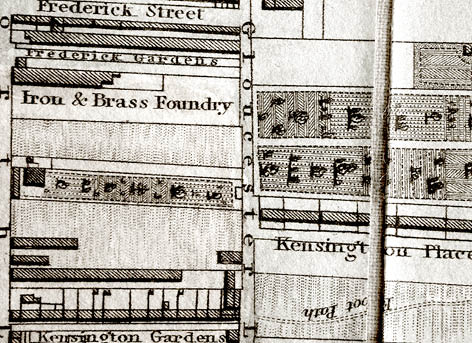

4) Detail from the 1826 J Pigot-Smith map. Image courtesy

of the Royal Pavilion, Libraries and Museums, Brighton and Hove

5) Detail from the 1842 Brighton ‘Reform’ map. Image

courtesy of the Royal Pavilion, Libraries and Museums,

Brighton and Hove

6) Detail from the 1845 “30 chains” map of Brighton and

Hove. Image courtesy of the Royal Pavilion, Libraries and

Museums, Brighton and Hove

7) Detail from the 1870 “30 chains” map of Brighton and

Hove. Image courtesy of the Royal Pavilion, Libraries and

Museums, Brighton and Hove

West side

In 1741 Richard Tidy passed to Thomas Scutt all the land he owned in the Common Laines, which had formerly belonged to Benjamin Masters. This land passed to Benjamin Scutt on Thomas Scutt’s death in 1755. On the bankruptcy and subsequent death of Benjamin Scutt in the early 1800s and since no heirs could be traced, Attree, who was the Steward of the Manor, took out Letters of Administration and the land was acquired by Thomas Kemp, John Wichelo and William Cooper in September 1822.2 In January 1846 Thomas West, James Vallance and Johns Wills, as trustees for the late Benjamin Scutt, sold the land identified as 19 in the 1738 Terrier (land survey) and 16 in the later Budgen Terrier, to William Stevens. (It is unclear at the moment what happened between 1822 and 1846 as records have not yet been located. It is possible that Scutt’s land was divided. In the 1792 Terrier Wichelo, Thomas Scutt and Thomas Kemp all have land in the Second Furlong.) Stevens’ land was identified as abutting on the West a four paul piece belonging to John Friends and later Nathanial Kemp, and on the East an eight paul piece, belonging to Thomas Kemp.3 This land was sold for £800 which is approximately £35,280 at 2005 prices.

William Stevens began developing the land almost immediately, quickly selling the properties and land. We have records for the development and sale of every house from 2 to 16 except No. 4.

In May 1847 William Stevens sold a piece of land “intended to be called Queen’s Gardens and all buildings etc now standing on it” to Thomas Over for £375. 13s. This land, abutting Gloster (Gloucester) Lane in the North, land of William Stevens in the South, George Cheeseman Childrens on the West and the intended road on the East, measured from N-S 122 ft and from E-W 35 ft.

This is approximately eight plots of land, but as further records pertaining to this purchase have yet to be located, it is unclear which houses Thomas Over built. From the description of the land however he could be the builder of numbers 17 to 23 Queen’s Gardens.

East side

Our history of the east side begins with a long printed document, watermarked 1833, which sets out the title of Thomas Read Kemp to land in the second furlong of North Laine. In May 1794 Thomas Kemp bought the land from Western’s at auction for £3,500 (£191,105 in 2005.) On his death in 1810 his properties passed to his son, Thomas Read Kemp, and to his brother, Nathaniel and the Reverend William Whitfield to hold in trust for Thomas Read Kemp. In April 1819 Thomas Read Kemp acquired all the land under the terms of the will.4

We have found no further records relating to the east side of Queen’s Gardens except the records of numbers 34 and 35. The beginning of this is the sale of part of the land to build these houses, but who built the rest of the east side has not been traced. In 1841 Kemp, having fallen on hard times, went to reside in ‘foreign parts’, appointing George Faithfull as his attorney, and in April 1842 he sold the land to Richard Edwards, who was previously his land agent and now a builder, for £400. The land was described as eight parts of land formerly owned by Westerns in the second furlong of North Laine. It was bound to the north by Gloster Lane, to the east by four parts formerly of Benjamin Scutt and to the west by eight parts formerly of Benjamin Masters. That would appear to be the whole of what was to become the east side of Queen’s Gardens.

Edwards then sold ‘an intended paysage 5 feet wide from North Laine to Gloster Lane’ in 1845 for £450 to Ewen Evershed and Stephen Gunn. The land measured 245 ft from north to south and 35 ft from east to west. The other part on the south, according to the deeds, was sold to a William Good. In July 1846 a 30 ft by 35 ft plot was sold to Burrows Beckett, a brick maker from Lindfield who went on to build two houses on this land, which abutted, to the south land belonging to Evershed and agreed by him to be sold to Thomas Over, to the North Evershed’s land in the occupation of Alfred Eastwood, and to the East Scutt’s land. Land strictly for gardens measuring 30 ft by 10 ft was also sold. Everything points to Ewen Evershed adopting the same approach as William Stevens across the road: sell off two-house plots and sell some to that speculative builder, Thomas Over.

Architecture and materials

The properties in Queen’s Gardens are, like those in neighbouring streets, constructed principally of Bungaroosh (a local Sussex name for flint and lime wall), brick, Roman cement, lime-plaster and timber. Although sharing this common set of materials, the street has a distinct and unique personality, one derived largely from the efforts of the original developers to give the facades a unified and often slightly gentrified character.

Almost all of the properties in the street are two stories above ground with basement, the exception being number 3.

The houses are principally finished with simple rendered elevations but some properties display elaborated detail. A small number to the south-west end of the street have fine, moulded, door cases and further north on the same side are to be found properties with rusticated ground floor facades (deep, wide, channels laid into the render). On the north-east side of the street some houses have brick elevations, which would have been expensive at the time the properties were built.

As is the case in a number of other North Laine locations, the developers of Queen’s Gardens were enthusiastic that their relatively modest dwellings might nevertheless share some of the same decorative styles that were being deployed for the gentry in the grand buildings around the town. As if to emphasize this, above the run-section stringcourses separating ground and first floor, some homes sport pilasters.

By far the majority of the houses would have originally utilized double hung sash windows with Georgian pattern glazing. Although, today, there is evidence of later Victorian window design, and relatively recent glazing intervention, many properties retain Georgian sashes.

Amenities and alterations

At present research into this area has been unsuccessful. We hope further investigation will help to provide some answers and information regarding the provision of gas, electricity, water etc.

Notable buildings

Queen’s Gardens does not have notable buildings such as a foundry or a chapel, but what does distinguish Queen’s Gardens from some of the other streets in the area is that so much of the original record regarding the building of the street has survived. For whatever reason, Stevens did not enfranchise the land and thankfully Tamplins the brewery kept records of the restrictive covenant protecting the pub at number 7. Equally, Eversheds, the solicitors, retained deeds relating to numbers 34 and 35. The rest, we must surmise from old maps, the Census records and the street directories.

Notable people

Jack Tinker the late theatre critic lived in Queen’s Gardens. A well thought of and respected critic and journalist, Tinker worked for the Evening Argus during the 1960s and was “the greatest out-of-London critic”5 eventually becoming the Daily Mail’s theatre critic, where he worked for twenty-five years. On his premature death in 1996 at the age of fifty-eight, the West End dimmed its lights in a mark of respect.6

Residents

Number 1

Adjoining the shop on the corner of North Road and Queen’s Gardens it moved quickly from private residence to commercial use. From the record of the building of number 1 Queen’s Gardens, it is known that in 1849 that the land was let by William Stevens to William Good and was occupied by a Spencer Weston.

8) Queen’s Gardens today

9) Queen’s Gardens 1928. Image courtesy of The Regency Society. For further details, see:

http://www.regencysociety-jamesgray.com

In the 1851 Census Oliver Weston, a grocer, was now the occupier, in 1859 Oliver Weston was recorded as both living and owning the house, however the address was noted as North Lane, an early name for North Road. In 1878 and 1879 numbers 1 and 2 are listed as The North Road Club lecture rooms and coffee room and thereafter designated in turn a grocers, a confectioners, a newspaper shop and by 1898 the building was an oil colour and paper hanging warehouse.

The Census summary of 1911 lists the property as offices. In 1918 the Directory refers to 1 and, newly listed, 1a, as wholesale newsagents and this can be seen in the 1928 photograph below.

By 1931, however, number 1 has disappeared from Queen’s Gardens’ directory listings once more.

Number 2

In January 1849 William Stevens sold the property to Thomas Bunce a carpenter, who was still resident in 1851 along with his wife Mary, an upholsteress and their daughters Sarah and Mary who was a dressmaker.7 From 1852 the property has many guises including that of a confectioners, a shirt collar makers and an undertakers. Interestingly, Ernest Belcher, who was a confectioner in 1931 had become an undertaker by 1937.

Number 3

At the same time as he sold number 2, Stevens sold number 3 to Richard Curtis. This house seems to have led a quiet life except that it was rebuilt in 1863. No plans have survived of this rebuilding but the building is one storey higher than the neighbouring houses.

10) 3 Queen’s Gardens today

Number 4

This house is shown in the 1851 census but the first occupant is in 1861. This is a paperhanger, Charles Patching and we might wonder if he was related to the builder, Richard Patching. We did not find a record of the sale of this house but it is most likely in the same Court Book as numbers 3 and 5.

Number 5

In June 1846 William Stevens sold to John Stevens, builder and furniture maker, the house, workshop and buildings for £200. John and family were still there in 1851 but not by 1861. Perhaps he made money and moved on. The house then led a quiet life, becoming a tailor’s for a while.

Number 6

This is another quiet house. It was sold by William Stevens to Benjamin Cox in January 1847 and along with numbers 7 to 12 and is probably amongst the earliest houses in the street. The peace of the residents may well have been disrupted by its neighbour at number 7.

Numbers 7 (and 8 until 1862)8

In August 1846 William Stevens sold to Stephen Drury a bricklayer, a piece of land measuring, 30 ft from north to south and 32 ft from east to west, together with the houses 7 and 8 (in the record the numbers are blank but it is known from subsequent records that they are numbers 7 and 8 Queen’s Gardens), and another 10 ft which was to be used as gardens or a green. Drury was also required to erect a dwarf wall, palisade or iron fence and to pay for a share of the paving of the road. (The houses are copyhold until 1871 but the alley freehold.) Drury bought the land and properties with £350 advanced by Edmund Vallance and William Catt.

In 1847, for £550, Drury sold the two properties, including the carpenter’s shop at the rear, to Charles Catt, who was acting on behalf of Vallance, Catt Brewers, Maltsters and Coal Merchants and this was the beginning of number 7’s career as a pub.9 In 1847 number 7 was listed, in the street directory of that year, as a beershop with a carpenter’s shop behind. The resident of this house, Thomas Tidey, was listed as a retailer of beer in the 1848 Folthorp street directory. In 1854 the house was known as ‘the Green Man’ and run by Thomas Oram but the Census from 1861 shows two households living at number 7 and neither are beershop keepers or publicans. The 1855 directory shows a beer retailer but there is nothing listed in 1864. The next listing in a street directory is in 1868 when Amos Cottingham is listed as beer retailer and in 1869 the pub appears in Mathieson’s Directory as ‘the Queen’s Tavern’. As part of the business management of Vallance, Catt Brewers, the house was enfranchised (the freehold purchased) in 1871 for £30 and the holding transferred to Mr Henry Willett (previously known as Henry Catt). It was valued at £400. Vallance, Catt traded as a partnership from 1871 until 1892, when Charles William Catt decided to trade independently. Catt took a number of licensed houses as his share of the dissolution and in 1899 sold them to Tamplins brewery and this included the Queen’s Tavern.

Amos Cottingham continued as the retailer at the Tavern for thirty years until the 1897 Towner’s Directory shows the resident at the Queen’s Tavern to be Ernest Greed. There are further changes to the proprietor until 1912, when there is no number 7 listed at all, let alone a tavern. Pikes had listed John Bishop at the Queen’s Tavern in 1911, although the 1911 Census shows Ernest Greed, publican as residing at number 7 and yet Greed, Bishop and the pub have disappeared from the records by 1912. In 1913 Pike’s directory informs us that Rudolf Furtauer was living at number 7. The Furtauers continued to live at the address through both World Wars. In 1960 Kelly’s directory lists only Mrs Furtauer and by 1962 she, too, was gone.

11) 7 Queen’s Gardens: the old Queen’s Tavern

Number 8

In August 1862 the skittle alley at the rear of number 8 Queen’s Gardens was sold off for £350 to become number 8 Foundry Street. At the same time the house, number 8, was sold by Charles Catt (brewer) on behalf of the firm to Charles Bishop (printer) for £170 but on the express condition that the trade or business of distiller, brewer, alehouse keeper, beershop keeper, victualler or tavern keeper, must not, at any time, be carried out on the premises. Also no beer, porter, wine spirits or other liquors were to be sold from the address.10 This was the first appearance of a restrictive covenant that lasted, certainly until 1910, although a similar covenant had been inserted into the indentures for sale on other parts of the North Laine.

In December 1869 Charles Bishop was paid £250 by Charles Burrell, a publican, for the house. Despite the fact that the purchaser was a publican, the restrictive covenant remained in place. The 1871 Census shows that a beermaker was in residence so it is possible that Burrell bought number 8 to house his employees.

During the first thirty-two years of its life tenants occupied the house, but in October 1878 the forces of law and order moved in next door to the pub. George Botting, a police constable, bought the house for £275, with a mortgage of £100 from the Sussex Mutual Permanent Investment Building Society. In 1891 George was living at the address with his wife, their two sons and three lodgers. If it was cramped in 1891, by 1901 it was even more so, as living there were two households; one of six including a baby, and the other of five, also including a baby.

Land reform in the Settled Land Acts 1882-1890 meant that George Botting, now retired and living at 39, Queen’s Gardens, was able to buy the freehold of number 8, from the trustees of the Lord of the Manor of Brighton and so after twenty-two years, in January 1900, he sold the house to WP Bolingbroke, gentleman, resident in Preston, for £350. The house had increased its value by £75 or 33.3%, but for George the profit was diminished by the £10 outlay for the freehold. Once again the house was let and continued to be so until 1911. Unfortunately Census reports after 1911 are not available to the public for one hundred years. Number 8 was sold by William Bolingbroke’s heir to Alfred Kent, a hardware merchant of Gloster Road, for £200 in March 1910. (This Bolingbroke appears to be the Master Traveller’s Draper, resident at no.11 in 1881.)

Numbers 9 & 10

In February 1847 William Stevens sold to Robert Pelling land and two dwellings erected by Robert Pelling for £110 and in January 1849 Pelling sold to Joseph Brown. Both houses were in multiple occupation of two families at least from 1851 to the last census record of 1911. In 1911 a little known concert artist James Freeling Wilkinson was shown as boarding at number 10.

Numbers 11 & 12

In January 1847 William Stevens sold to Alfred Martin the land and two houses (which Mr Martin built) for £140. The houses were in multiple occupation but in 1881 William P Bolingbroke, a Master Traveller’s draper was living at number 11 with his wife, their child and servant – they were the only family at the address. Mr Pollard lived at number 12 with his family and he was a tailor. By 1891 Mrs Pollard was widowed and John Wilson, a draper’s traveller was living at number 11 with just his wife and child - by this time Bolingbroke had moved and the house was let. In Pike’s 1896 directory the business still appeared to be with Bolingbroke but by the 1897 Directory it was in the name of John Wilson, and it continued to be listed until 1940.

William Bolingbroke must have been prosperous. He lived only with his family for his brief stay in Queen’s Gardens and then we find he moved to Preston Park, calling himself a gentleman and buying property. Indeed, drapery must have been prosperous. If we follow the career of John Wilson we find that in 1896 Pikes Directory he is listed as a draper at no 31. 1897 Pikes Directory he was also at numbers 11 and 31. There is also a tailor at no 5 and a tailoress at no 30: were they all connected? By the 1901 census John Wilson has moved from 11 and is living at no 31, but by the 1911 census he is no longer living in Queen’s Gardens.

Numbers 13 & 14

These houses were built by Henry Penfold and sold to him with the land by Stevens in December 1849 for £400. In April 1850 Penfold sold on to Michael Maynard for £325. They were in at least two household occupancy for most of the period until 1911.

Numbers 15 & 16

The bricklayer Stephen Drury bought the houses and land from William Stevens for £250 in November 1849 and in 1851 was recorded as living at 15 with his wife and child. He was from Brooklands in Kent and was just 30 in 1851. Was he a very enterprising young man of 25 who also built, bought and sold numbers 7 and 8? In any case, he lived there with no other family and by 1861 was no longer living there. Number 16 was occupied by two families for the period until 1911 and by 1881 no 15 was in the same position.

Numbers 34 & 3511

In July 1846 Burrows Beckett, a brickmaker of Lindfield, with a mortgage of £200 from Richard Patching, a builder, bought from Ewen Evershed, Thomas Compton and John Vallance part of the land intended to be called ‘Queen’s Gardens’, bounded in the north by land belonging to Thomas Hodson. Beckett continued to pay the mortgage until 1849.

In October 1849 Burrows Beckett sold the land and two houses, which he built himself, to Daniel Haylarr, a carpenter. Haylarr never lived at either number 34 or 35 but mortgaged the properties for £407 in 1849, for £156 in 1856, for £300 in 1857 and for £128 in 1861. This pattern would indicate he was raising money to build and earning income from renting the two properties. In 1863 Haylarr again mortgaged the two houses to secure £220 to buy furniture: William Attree supplied both the mortgage and the furniture. He repaid all mortgages after a few years of taking them out and before taking out another, in 1866 Haylarr mortgaged numbers 34 and 35 Queen’s Gardens and his own home, 9 Oriental Place, for £1500, which he repaid by 1878, by which time he was running a boarding house.

Haylarr died in July 1887 and Nobbs was appointed as his trustees. In August 1946, they sold to a Mr Sergeant for £865. Sergeant died in March 1964 and in June 1968 his heirs transferred the property to Elizabeth Conway for £1000. Records after this transaction have not yet been found.

Trade

In the early years of its existence Queen’s Gardens housed servants, cooks, porters and others, as well as those who had a craft or a trade which they plied, either in the home or perhaps elsewhere. For example, the first inhabitants listed in the 1848 Folthorp street directory were a beer seller at number 7, a milliner and dressmaker at 37 and a baker at 41. Nearby Sydney Street and Tidy Street would have provided the residents of Queen’s Gardens with shops for their basic needs, e.g. a butcher and greengrocer. In the late 1870s Queen’s Gardens was also home to a manufacturing jeweller and a dairyman, and in 1891 a midwife had moved in.

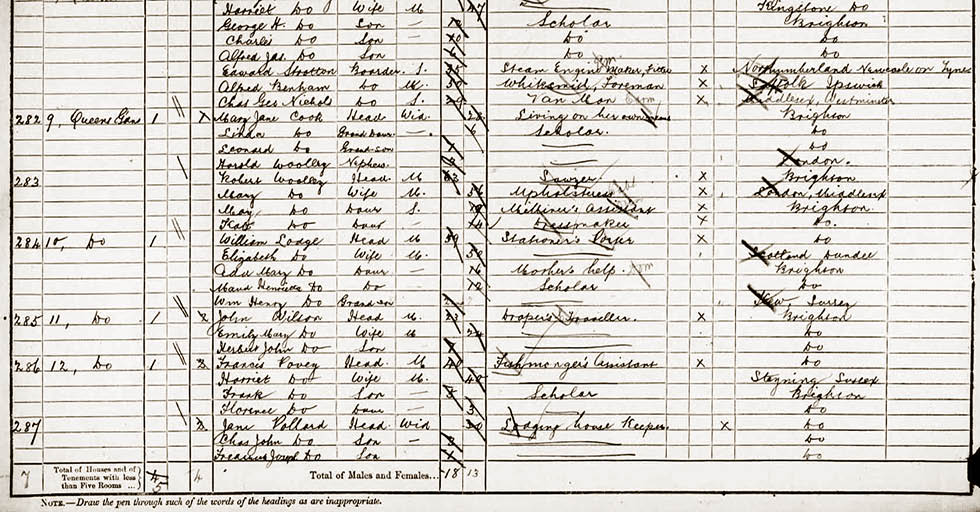

A read through the occupations listed in the Census reveal no unusual activities and most are recognisable today, although now they may be carried out in places far away from Queen’s Gardens and by a machine rather than a person. What is interesting is to see how the local employment is reflected. There is always someone connected with the railway, although never as exalted as a driver or stationmaster. There are printers, compositors and bookbinders and there are people connected with the theatre.

12) Detail from the 1891 Census for Queen’s Gardens. Image courtesy of The National Archives, London, England

Health

These people lived close to each other: not only did they live in small terraced houses but the houses were often in multiple occupation; at least two families to a house, and the families were not necessarily small. Given that they probably shared a single tap and an outside privy, the conditions must have been very different from now. The smell of people, privy and food – let alone the slaughterhouses in nearby Vine St; the ease with which disease could spread; the lack of gardens and places to hang out washing easily will all have contributed to a life in which keeping clean was more of a struggle than now.

Social life

People would have had little time for a social life as we might know it today. Working hours were much longer, often including Saturday and Sunday would perhaps demand a visit to church. The pub at number 7 would have been the main form of entertainment for Queen’s Garden’s residents, although it can have been a drinking place only; some of the pubs in other streets may have provided more entertainment. Social life might have revolved around the church, perhaps some political debate, and the introduction of the North Road Club Lecture Room in 1877 at number one would have provided residents with another opportunity to escape the home and work.

Conclusion

During the early years of its existence Queen’s Garden’s was like other streets in the North Laine; peopled by tradesmen, craftsmen, servants and labourers. There were plenty of children, some shops and a pub. It is a very Victorian tale and even when North Laine started to decline as an area there is no record of houses being condemned or of being compulsorily purchased as in some of the other streets. Today the street is pretty and well kept and even a little prosperous; it has become a chic Brighton address.

References

- ESRO, Court Books, Manor of Brighton. Ref. BRI66

- ESRO, Court Books, Manor of Brighton. Ref. BRI66, XA32/10

- ibid

- ESRO, 34 and 35 Queen’s Gardens, Brighton. Ref. ACC5310/246 1676-1968

- Unknown., (October 1996), Obituary: Jack Tinker http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-jack-tinker-1360766.html [Accessed 4th September 2011]

- Fuller, J., (2008), Jack Tinker of Queen’s Gardens on http://www.nlcaonline.org.uk/page_id__540_path__0p111p.aspx [Accessed 4th September 2011]

- ESRO, BRI66, XA32/10

- ESRO, Records of Tamplins Brewery, TAM/8/14/19

- Tamplins Property Register TAM8/5/2.

- ESRO, TAM/8/14/19

- ERSO, ACC5310/246