Trafalgar Street

Lead researcher Ian Walden

With additional research from Richard James, Helen Reynolds & Judy Woodman

Introduction

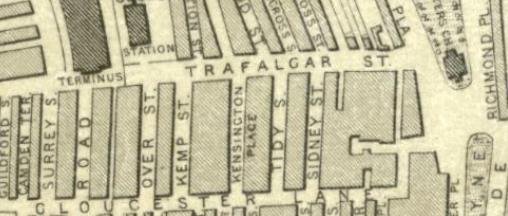

In present-day terms, Trafalgar Street runs along the north side of Brighton’s North Laine conservation area. It runs downhill, due East from the station, heading towards York Place and St. George’s Place, where it emerges near St Peter’s Church.

1. Brighton Parish, c.1740.

Image courtesy of Berry, S., ‘Brighton in the Early 19th Century’

in Leslie, K. and Short, B., eds. An Historical Atlas of Sussex. Chichester: Phillimore, 1999, p. 94

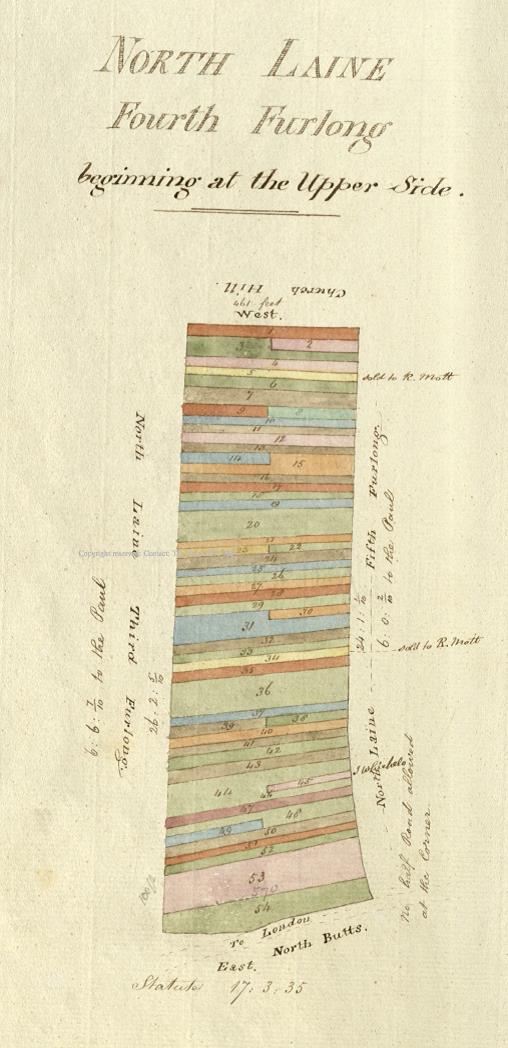

In 1738, the land survey of Brighton, known as the terrier, showed five tenantry ‘laines’ or large, open-plan fields. Named West Laine, Little Laine, East Laine, Hilly Laine and North Laine, they surrounded the town of Brighthelmstone, the old name for Brighton. These laines were divided into furlongs separated by narrow ‘leakway roads’ running east to west. Trafalgar Street is one of these leakways, dividing the third furlong to the south from the fourth furlong to the north.1 The furlongs were themselves divided into narrow strips called ‘paul-pieces’ running north to south, at right angles to the leakways. The modern-day street pattern in the North Laine area is based on this fossilised open-field system.

Trafalgar Street’s function as a boundary has continued to the present day, separating the ward of St Peter’s to the north and St Nicholas’ to the south.

2. Trafalgar Street looking West, c. 1900.

Image courtesy of Step Back in Time, 36 Queens Road

Development

Brighton’s development in the eighteenth century from a poor fishing town to a fashionable resort meant population growth and selling of agricultural land for urban development. The terrier of 1792 illustrates the strips, or paul pieces, in the third and fourth furlongs, and lists the owners of each paul. The owners are all familiar names in land ownership and development of the town: the Duke of Dorset, Thomas Kemp, Nathaniel Kemp, C. S. Dickens, Thomas Scutt, Mr Whichelo, Mr Hicks, Mr Mighell, Mr Ackerson, Mr Buckoll, Mr Michell, and Mr Halls. Thomas Kemp owned over a third of the land abutting what is now Trafalgar Street.

3. Terrier map of Brighton, Third Furlong, 1792. Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office

4. Terrier map of Brighton, Fourth Furlong, 1792. Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office

The 1822 Baxter’s Street Directory refers to this thoroughfare as ‘Trafalgar Place’, a name which survives in a legal indenture of 1833.2 Baxter’s lists only 7 properties in the street, and we can see from J Pigot-Smith’s map of 1826 that these few houses were mostly at the eastern, lower, end of the street, near the open area of the Steine.

5. Pigot-Smith map of Brighton, 1826.

Image courtesy of Brighton History Centre

The real impetus to the development of Trafalgar Street was the arrival of the railway, with the London to Brighton line opening in 1841. By 1845, when Queen’s Road was built to improve access to the station and a bridge was built across the entrance to Trafalgar Street, Kelly’s Directory was able to describe a full street of 112 properties. The railway was not in universal favour, however. Correspondence survives from 1847-1849 between Mr MB Tennant of no. 51 and the Town Commissioners. He laments the crumbling state of the arched wall supporting the railway on its eastern side, complaining that the props used were causing cracks in garden and house walls, that gaps at the top allowed rainwater to pour down into residents’ gardens and flood their cesspools, and that a large quantity of construction rubbish had been left on his property. His requests for compensation were without avail.3

The lower goods-yard to the east of the station was laid out in the 1840s, closed in the 1970s by British Rail, and subsequently used by National Carriers Ltd for a further ten years.4 Its original position can be seen in the 1852 Rapkin map below. A railway goods shed was built next to the station in the 1890s. The whole area was bought by Ewbank Preece Ltd in 1981, and developed into the office complex now called Trafalgar Place.5

6. Rapkin map of Brighton, 1852. Image courtesy of Brighton History Centre

Plans for Redevelopment

In 1959, the Brighton Corporation issued the first of several Compulsory Purchase Orders that would affect development of the north side of Trafalgar Street.6 Planned construction included a car park (now entered from Blackman Street) to serve the railway and the London Road shopping centre, and widening of Whitecross Street to 60 feet, as the first step in creating a north-south thoroughfare to relieve congestion on London Road.7

At the time, the only property affected was the Beehive Inn, then at no. 85 Trafalgar Street, which was scheduled for demolition to enable Whitecross Street to be widened. Although the Beehive was spared inclusion in the final draft of the CPO, its owners, Tamplin’s Brewery, were alarmed by the prospect of losing properties. Their alarm was heightened when their letters received the reply that “there is no doubt in the future that many public houses will have to be acquired by the Corporation in the course of comprehensive redevelopment, particularly in the area between Church Street and New England Road.” This indicates that wholesale demolition of large swathes of the North Laine was firmly on the Corporation’s agenda in the late 1950s.8

Tamplin’s did eventually sell the Beehive to the Corporation in 1967, without need for a CPO. Along with much of Whitecross Street, it was demolished. Like the railway, this was not a project without lasting repercussions. The neighbouring property, no. 84, was left with only a 4.5-inch party wall between the residents and the outside world. After her husband’s death, Mrs Lazenby faced an ongoing battle throughout the early 1970s to have the wall strengthened, cracks repaired, and damp prevented.

The same era saw plans for the expansion of Brighton Technical College, including a new engineering and science block in the site between Whitecross and Pelham Streets. In connection with this scheme, the Brighton Borough Corporation purchased nos. 86-88 in November 1962,9 and issued a CPO covering nos. 89-91 and 92-97 Trafalgar Street in 1973.10

At the time, construction was intended to begin in 1975. However, objections from residents delayed the process into 1974, and the local government reorganisation of that year (by which many Borough Corporation powers and projects were transferred to East Sussex County Council) led to further delays. By this time, Department of Education funding cutbacks were already public knowledge, casting doubt on when properties would be required, and building work begun. The council had vacant possession of no. 91, but antiquated layout made residential quarters difficult to let, and in no. 90, squatters had taken residence.

Owners of the other properties could neither sell nor risk investing in upkeep, and the 1970s were a period of decline for the street as a whole. The Brighton Gazette reported traders’ anger in its edition of 27th February 1976. They complained that ESCC-owned properties were not being demolished or let, failing to earn rent for the council and deterring customers from the street by their empty, dilapidated appearance. Final confirmation came from the ESCC Estates Department in September 1977 that the CPO ‘notices to treat’ were being withdrawn, and would no longer be required by the council. Apart from no. 86, which had already been demolished, the remaining Trafalgar Street properties remain intact to this day.11

7. Entrance to City College, showing original buildings on right

and newer developments on left, 2015. Image courtesy of I. Walden

Conservation Area

By the early 1980s, the whole North Laine had been declared a Conservation Area, with protection in law from large-scale redevelopment. New developments would be required to show sensitivity to their local surroundings. We can see this in the 1983 presentation compiled by RHWL, the architects of a new office complex for Ewbank Preece Ltd., on the site of the old railway goods shed.

In support of their planning application, they are at pains to show how they have taken into account both the scale and style of buildings in Trafalgar Street, and the need for their development to provide a transition from the large structures of the railway, the Comet warehouse in Station Street, and the Theobalds House block of flats on Blackman Street, into the older and smaller buildings below. As such, the frontage to Trafalgar Street is noticeably lower in height than the offices behind, allowing light in, and replacing the goods shed’s supporting wall (an imposing structure covered with advertising hoardings, as shown in a photograph within the presentation) with shops and residential spaces in a scale commensurate with the rest of the street.12

8. The goods shed before redevelopment, 1983. Image courtesy of the Regency Society

9. The site redeveloped as Trafalgar Place, 2015. Image courtesy of I. Walden

The 1990s saw a variety of temporary, experimental traffic orders in Trafalgar Street, recognising the North Laine’s increasing prosperity, not only as a through-route between the railway station and the London Road, but as a pedestrian-friendly shopping venue in its own right. Traffic was made one-way between Tidy Street and Frederick Place, and prohibited entirely for a time at the lower end of the street, near York Place.13 At the time of writing, the present arrangement is that traffic flows westbound only from York Place up as far as Sydney Street, and in both directions higher up. There are no pedestrianized sections.

Architecture and materials

The Pevsner Architectural Guide describes Trafalgar Street as being characterised by “small-scale nineteenth-century industrial buildings and artisan housing, mostly opening directly to the street.”14 The surviving structures are mostly 2- or 3-storey buildings, with a shop on the ground floor, often below 3-sided bay front windows. A few bow windows, possibly indicating slightly earlier properties, can be seen, for example above the undertakers Newman & Stringer at number 3, and above Cafe Electronica at number 15.

However, there were once much grander houses with large gardens at nos. 98 and 99, forming the north side of Pelham Square. Indeed, their residents, Thomas Carter and Daniel Hack, were the developers (along with George Lynn) of Pelham Square itself.15 So, the social and architectural mix of Trafalgar Street was more complex in the nineteenth century than the surviving buildings indicate.

Listed buildings include nos. 11-12, included as part of the Pelham Square development, number 48 (the Prince Albert public house), and nos. 96-97, formerly one property but now an antique shop and brasserie, respectively, on the west side of Pelham Street.

The Prince Albert dates from the 1840s, a 3-storey building “with round-headed windows, and Corinthian and Ionic pilasters, the capitals being highlighted in gold paint.”16 Most people know it for the two artworks on the west-facing wall, the portrait of John Peel and the kissing policemen by Banksy.

10. Building Alteration Plan for the Prince Albert, 1881.

Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, ref. DB/D/8/2127

Also grade II listed, 96-97 Trafalgar Street and 1-2 Pelham Street were for a long time one single property, as can clearly be seen by looking at the residential quarters at first- and second-floor level. Throughout the nineteenth century, glass-making technology, fashion, and salesmanship drove a desire for larger and clearer shop windows. By 1902, this shop, like many others, already had large plate glass windows supported by iron frames. The drapers Messrs Bundock & Son had the corner doorway removed at this time, and a new entrance created in Pelham Street, paving the way for future division of the shop. Removing the doorway, and replacing it with glass, meant the weight of the rounded brick wall above could only be carried by inserting a steel girder above the window.17

11. No. 96-97 Trafalgar Street, 2015. Image courtesy of I. Walden

Similar shop-front improvements can be seen at nos. 100-102, leased for some time by George Taylor, a plumber. In 1867 he added the large window at no 102 onto Trafalgar Court.18 Two years later he replaced brick ground-floor shop fronts (with rounded bow windows) at nos. 100-101 with the flat plate glass and angular inset doorways we see today. He also added canted bow windows above, to match no. 102.19

The decorated style of the Great Eastern at no. 103 dates from 1895 when Tamplins Brewery had the wide bow window on Trafalgar Street, and the entrance from Trafalgar Court, removed. They replaced them with narrower, more protruding, flat-fronted windows and the pub’s trademark rounded corner entrance. At the same time, the upper windows gained arches and by-then antique style 9-pane sashes, and were surrounded by inset panels.20 This decorative design and the projecting windows were then complimentary with the 1868 shop front of no. 104, for Mr P Lelliott (now Rare Kind Records); a comparison that is not so easily made at the time of writing.21

12. Building Alteration Plan for the Great Eastern, 1895.

Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, ref. DB/D/8/4095

13. The Great Eastern, 2015. Image courtesy of I. Walden

Ownership Patterns

The papers of the Revd. John Nicholl, vicar of Westham, lists 74 properties comprising his Brighton Estate, which includes number 4 Trafalgar Street, suggesting that houses and sometimes whole streets were developed speculatively and leased out to working families eager to find accommodation where they could both live and very often also run a small business, frequently supplementing the family income by taking in lodgers.22 At the grander end, the Hack family continued to own numbers 98 and 99, leasing one and living in the other.

From aristocrats to tradesmen

Conveyance indentures typically refer to previous landowners, and it is noticeable that the further back in time we look, the more aristocratic are the owners of property in what is now Trafalgar Street. The deeds of what is probably no.2 make reference to previous leases as far back as 1819, when parties to the legal exchanges included the fabulously wealthy widow, Arabella Diana, Duchess of Dorset.23

Later development, from the 1840s, was often undertaken by property developers such as Robert Chalcroft and Joseph Fricker, whose names appear amid the deeds of nos. 25 to 35.24 Several of these properties have very detailed extant ownership records. Of particular interest is Zacceheus Anscomb, a farmer’s son born in 1804, who at the time of his second marriage in May 1854 was living at no. 75 (now The Dressing Room) and whose occupations are variously listed as chandler, miller, and baker. His work had enabled him to buy nos. 31 and 35, and by the time of his death in 1869 he was able to leave his wife Barbara these properties and also 33 Blackman Street – a sizeable inheritance for a working man.25

Reasons for ownership changes

The most accessible ownership histories exist for properties bought by the town or county authorities for demolition and rebuilding. As such, the Record Office holds a number of fascinating histories for properties that no longer exist, particularly those on the north side of Trafalgar Street. They illustrate a wide variety of reasons why properties change hands. One of the most notable features from today’s perspective is the utter absence of banks in any of the transactions. Mortgages, leases, and other transfers were largely arranged between family or business connections, without the need for financial intermediaries.

The land formerly occupied by no. 85 passed by inheritance through the family of London lawyer Anthony Dickins between 1773 and 1822.26 By 1837 a dwelling had been built, and the property repeatedly leased to a series of craftsmen and merchants. In 1873 it was sold to James Tourle, a grocer, who leased the property as a pub named The Beehive to Messrs Warde (a Kent farmer) and Thompson (brewer). By 1888, however, Tourle was bankrupt, and a public auction was held at The Old Ship Hotel on 18th October to sell off his widespread property holdings. The Beehive was lot 12 of 18, described in detail with its “commodious bar, smoking room, wash-house” and “large dry cellar.” Part of Tourle’s financial problems may have been due to the long, fixed-rate leases that were normal for the time; the Beehive was let for 46 years, “at the very inadequate rental of £55 per annum,” expected to rise to £100 p.a. when the lease was renewed. The pub was bought at the auction by large local brewers Kidd & Hotblack, passed to Tamplins in the course of business consolidation, and was sold to Brighton Corporation for demolition in 1967, to enable the widening of Whitecross Street.

The home décor shop ‘Swag’ at number 91 was, like no. 85, owned during the 1820s and 1830s by local worthies such as Thomas Attree and ‘land surveyor’ Thomas Budgen.27 By the 1850s it passed through the hands of John Allcorn, who cannot have been resident, since his address is given first as Lambeth, Surrey, and later as Hackney, Middlesex. He leased the property to the Emerys, grocers. In 1877 Allcorn changed roles, selling the freehold to Peter Emery, but providing him with the mortgage that enabled him to buy. His trust was misplaced, however, as Emery took the common course of repeatedly mortgaging the same property to different lenders. In 1880 one of these, Henry Corney, ultimately enforced the property’s sale to the lessee, Alfred Earl, a bootmaker, with neither he nor Allcorn getting all their money back. Between them, Earl and his wife Ann held the property all their lives, until 1934, although by this time they lived in Portslade and in 1923 had let the property to John Hay. He must have bought the freehold at some point, as Hay & Son Ltd were listed as the owners and occupiers at the time of the 1973 Compulsory Purchase Order by Brighton Corporation.28

14. Number 91 Trafalgar Street, 2015. Image courtesy of Ian Walden

Extensive histories also exist for nos. 98 and 99, donated to the Brighton School Board in 1906 to enable an extension to the York Place Elementary Schools. These were large mansions with gardens, built on originally huge plots of land, extending 190 feet to the north of Trafalgar Street. Number 98, known as Trafalgar Lodge, was built by William Wood around 1831, before he sold it to Thomas Carter, a confectioner. His father James had bought no. 99 in 1812, and by 1851 Thomas was describing himself as a farmer from Hurstpierpoint, redefining himself from wealthy merchant’s son to landed gentry.

Upon James’ death in 1847, Thomas and his sister Mary had sold their stake in no. 99 to Daniel Pryor Hack, with whom, and with George Lynn, Carter developed Pelham Square in 1851. However, Carter clearly needed cash, mortgaging no. 98 to his new neighbour Hack for £1,500, a loan on which he defaulted within only a few years, forcing the sale of no. 98 in 1857 to Miss Mary Prier. She paid only £1,100 (to Hack, as mortgage lender) for the house, which at her death in 1879 Hack purchased for himself for £2,040. Even for a man of Hack’s huge wealth, the £400 loss made on the house in those early years was a substantial sum, raising the question why it was sold at so low a price – perhaps Prier was a family friend, or fellow member of the Quaker community, to whom Hack would rather sell than attempt to get more money at auction.

DP Hack left both houses to his daughters on his death in 1886, leaving cash to his infant son Daniel. Upon his majority in 1906, Daniel bought the freehold from his sisters, donating the properties to the School Board that same year.

15. Numbers 98-99 Trafalgar Street, 1953. Image courtesy of the Regency Society

Amenities

It was not until the 1860s that it was understood that cholera was water-borne, and drainage became an urgent issue, not only in London, but also in Brighton. We have one reference to an earlier sewer plan, dated March 1845, but the researchers of this history have been unable to view the plan itself.29 Between 1856 and 1858, the Borough’s Works Committee considered several requests for drains in Trafalgar Street to be connected to the main sewer. Many, though, were for surface water only. One drain requested ran from the Prince George Inn in the new Pelham Square, while another, granted to Mr Attree in 1857, used a 9-inch pipe drain at numbers 15 and 16.30

Creating a system of public lamps was a key job of the town corporation, and the first plans for Trafalgar Street are dated December 1860.31 Private lamps continued to be in use for some time, however. In 1883, the first year for which we have minutes of the town’s Gas Committee, a letter was received from Mr Gardner. As proprietor of the ‘Beehive’, he wrote to the corporation to request the removal of the public lamp from his wall as he proposed to place a show lamp there.32

The disposal of ashes from open fires, cooking ranges and light industry was a problem in Victorian towns and although some partial supply must have been available for lamps, it was not until 1885 that plans for proper gas mains in Trafalgar Street were drawn up. The pipes were to run along the centre of the street from York Place up as far as Sydney Street, including the side streets such as Pelham Square.33

Notable buildings

Pubs

Being a major commercial thoroughfare for much of its history, Trafalgar Street contains a number of significant and interesting buildings. Many of the properties are or have been public houses for at least part of their history, and it is with these we begin.

The Prince George at no. 5 was “originally a dairy, becoming licensed in1820, selling milk & beer, & still called Prince George and Cowkeeper as late as 1846. A section of the pub’s cellar once used for body storage by a nearby undertaker.”34 A scrapbook held in the Record Office contains a list of landlords for this pub, and all those below, which for the Prince George stretches back to 1843.35 In 1857 it was taken over by local brewers Vallance and Catt, who immediately extended the building’s frontage.36 Charles Catt took out a new 20-year lease on the building in 1872, at the substantial annual rent of £96.37 An 1895 inventory of the property of Henry Willett, including many Sussex pubs, shows a plan of the premises including a bow window to the left of the front door, and the rear courtyard.38 By 1900, when a new licence was issued, Vallance & Catt were using their West Street Brewery name.39 It indicates a period of great consolidation in the local brewing industry that by the time the two front bars were knocked through into one space, in 1933, the client was the Kemp Town Brewery.40 The pub has been famed, at least since a 1993 advertising flyer was produced, for its ‘extensive vegetarian and vegan menu’.41

Little evidence of ownership or architectural alterations exists for the Lord Nelson at no. 36. Landlords are listed from 1858,42 and the pub was clearly a significant meeting venue in 1913, when on Friday 29th August Mr EH Jarvis was due to address a meeting of the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners.43

At no. 38, the building currently occupied by café ‘Toast of Brighton’ was once home to the South Coast Tavern. Its proprietors were described from 1858 onwards as ‘grocers’ but from 1880 as ‘beer retailers’.44 Owned in its early days by Messrs Smithers & Son,45 the licence was eventually surrendered voluntarily by the Kemp Town Brewery in 1950.46

The cycle shop ‘Velo Vitality’ at no. 44 was the Harmonic Tavern from 1858, with a change of name to Western Star in 1880.47 Owners Kidd & Hotblack had to find a new licensee in 1908 after Henry Meakins was convicted of two offences in three years. In June 1906 he was found guilty of selling intoxicating liquor during prohibited hours, and fined £1 and costs or 14 days imprisonment. In May 1908 he was convicted of selling beer to a drunken person, fined 50 /- and costs or 14 days imprisonment. This must have been the last straw, as within the year the new occupier was one Thomas Henry Gaston.48 The pub was in Tamplins hands from 1926, and they surrendered the licence in September 1933. A note in the Tamplins Property Register, stating “30 licences to be surrendered in 10 years, 1933-42” indicates that this was part of an organised mass surrender, presumably imposed on various brewers (Tamplins list not only their own surrenders, but also those of their rivals Kemp Town and Rock breweries) for some reason.49

16. The ‘Velo Vitality’ cycle shop, formerly the Harmonic Tavern, later Western Star, 2015.

Image courtesy of I. Walden

The Prince Albert at no. 48 was functioning as a pub by 1843,50 and was branded a ‘hotel’ on the 1881 design for new windows, for then-owners Vallance & Catt.51 Around the same time, the landlord was one A. Giuliani, who in 1882 advertised the hotel’s ‘choice cigars’ and ‘good beds’, an advertisement bearing the freemasons’ emblem, indicating his business connections within the town.52 In 1937, the hotel was using a rather different advertising approach – customers were invited to come and witness the table-laying and drinks-collecting tricks performed by Alf Appleton’s spaniel, Peggy, whose exploits had first been broadcast in an article from ‘The Star’ of 22 August 1934.53

Directly across from the Prince Albert once stood the ‘Holly Bush’, where now only a bridge extension and the rear of an office complex can be seen. In 1864 it was still known as Trafalgar House, in the ownership of one Charles Kemp, a builder, but already it must have been used as a pub, since its ground plan included a tap room and a parlour.54 During the 1880s and 1890s its licence was renewed under the ownership of the London, Brighton, & South Coast Railway Company,55 although an 1892 re-building plan gives the client as “W. Willett, Esq.”56 The last proprietor as a ‘beer retailer’ is listed in one scrapbook against a date of 1969.57

17. New building plan for the Holly Bush pub, 1892.

Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, ref. DB/D/7/2883

While other pubs existed west of the railway line, the next inn on what is now Trafalgar Street was the Coachmakers Arms at no. 76, on the site where Caffe Aldo in its modern premises now stands. Initially owned by Kidd & Hotblack, Tamplins took it over in 1926. Back in 1894, it was an outlet for the ‘Celebrated Ales’ of Frank Ballard & Co., of Lewes.58 An advertisement to this effect was placed by Mr E Boxall (“late of the Chain Pier Restaurant”), a recent replacement for Cephus Goldring, who in May of that year was convicted “of using his licensed premises in contravention of the Act … for the suppression of Betting Houses … and fined £10 or one month’s imprisonment.”59 An advertisement from 1959 proudly proclaims its “Well Stocked Bars,” “Tasty Snacks,” and “Comfortable Lounges,” as well as its location, perceived to be not a destination in its own right, but being “On the Road from the Station to the Popular London Road Shopping Centre.” Always a small corner premises under residential first-floor quarters, by 1984 it was the first pub in Brighton tied to the new “Raven” brewery in Vine Street. A 1989 photo shows its windows boarded up.60

18. The Coachmakers Arms, c. 1899.

Image courtesy of Step Back in Time, 36 Queens Road

Kidd & Hotblack’s ‘Beehive’ pub at no. 85 has been amply discussed above, under ‘Ownership Patterns’. This leaves the grand edifice of the Great Eastern at no. 103. Granted its wine licence in 1851 and a full licence two years later, this was an early Tamplins purchase, being taken over by them in 1896.61

Other Buildings

Besides the pubs, mention must be made of three other premises. The first is no. 41. Around 1890, when it appears in Page’s Directory under the auspices of Mrs L. Pollard, it began to be used by the Quaker community as a Mission. It hosted Sunday evening services, as well as adult schools for both men and women during the day on Sundays, and various meetings during the week. Further details of these can be found below under ‘Life and Work’.

The Quaker community purchased the premises for £1,150 in 1893, with Mary Hack giving £400, other local Friends £50, and the remainder being financed by the sale of an old burial ground to the Corporation.62 In the 1911 Census, we find the Bristows living above the Mission Room, where Alfred worked for the tramway corporation and his wife Jane was caretaker of the Mission Society. The Trafalgar Street Society of Friends Mission Hall was sold in 1945, with part of the proceeds helping the Eastbourne Quakers rebuild their meeting house after damage sustained during the war.63

The 3-storey building on the corner of Trafalgar Terrace now houses St Noah’s News, an off-licence; an ironic change of use, since many Quakers promoted temperance. Daniel Hack Jnr. once carried barrels out of a public house in the town and poured the contents down the drains!64

19. Noah's News, formerly the Friends' Mission Hall, 2015.

Image courtesy of I. Walden

The garage at no. 47, now home to Thrifty Car Rentals, is notable more for what might have been than what is present now. Built on the old inn yard of the Prince Albert, the building was designed as the “Golden Butterfly Garage” for F Bevan, in 1924. While the coach yard, lock up shops, and steel framed roof appear now as then drawn, we are missing the living quarters and neo-Tudor design originally intended.65

20. Building plans for the Golden Butterfly Garage, 1924.

Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, ref. DB/D/7/6751

The Station

Finally, no discussion of Trafalgar Street can be complete without mention of the Station. Brighton Station was designed by the Jewish architect, David Mocatta (1806-1882), a pupil of Sir John Soane. Mocatta became the official architect to the London and Brighton Railway and the railway station was his first commission for the company. The station was opened on 11 May, 1840 and the main building was completed by the time the first train from London arrived, on 21 September 1841. The station was built on an artificial chalk platform and its Italian style was designed to blend with the aesthetic of the town and avoid a detracting industrial architecture. Its building was a vast undertaking, involving 3,500 men and 570 horses. Part of the original main terminus building can still be seen behind the later canopy at the front. The original had a nine arch arcade at the front elevation, framed by adjacent pavilions with screens of columns, which can still be seen, albeit obscured by later accretions.66

21. Brighton station, 1841. Image courtesy of the Regency Society

The original station was built before the bridge and Queens Road, which were added in 1845. Until these were completed, hackney cabs had to climb Trafalgar Street, but the top section was and is too steep for horses, so a cab road was built along the side of the station. As the 2008 Pevsner guide remarks,

“the tall arch at the bottom of the building on Trafalgar Street leads to the former hackney carriage road, a quarter-mile of surviving late Victorian street, which runs in semi-darkness, lit by occasional arches in the side of the station, up to the end of platform six.”67

22. Entrance to hackney carriage road, 2015. Image courtesy of I. Walden

The road was later covered over by the 1882 extensions (when the present iron and glass train shed was added), but the entrance doorway can still be seen on the North side of Trafalgar Street, just below the bridge. Behind the doors, the road can still be seen, complete with ruts in the cobbles from the cabs’ metal wheels, and the wear in the brickwork where cabs waited for the arrival of trains. The road contains a right-angled turn, to bring the last part alongside the arrivals platform. With the advent of horseless carriages, which could not turn in this restricted area (but could manage the steep section of Trafalgar Street under the bridge), the cab road as a whole fell into disuse.

Residents

The Hack family

Invisible to the modern eye, Trafalgar Street contains elements of many strands of Brighton history, tied in to the growth of the town in the nineteenth century, and one of them is the development of non-conformism and the influence of philanthropic businessmen who were involved in the thriving economy of Brighton.

Quakers flourished in Brighton with the openings for trade and apprenticeships. This was in spite of the inconvenience of distraints, the fines for refusing to pay church dues and military rates.68 Quaker families often intermarried and went into business partnerships with each other. One of the entrepreneurial hierarchies was the Hack dynasty from Chichester. Daniel Hack, a linen draper in East Street, married Sarah Pryor and was instrumental in the development of the “New Road” from East Street. Their son Daniel Pryor Hack (1794-1886) can be found living at 99 Trafalgar Street in the 1841 Census, with his wife Elizabeth, daughters Priscilla and Mary, son Daniel, and three servants. In his youth, Daniel Pryor Hack had worked with Grover Kemp to establish the Brighton Savings Bank, a so-called “Penny Bank” for poorer people, to enable them to save small sums of money, as well as being active in the anti-slavery movement. It was this Daniel Pryor Hack, with Mr Carter and the builder Mr Lynn, who together bought the land for the garden which became the centre of Pelham Square. His property, 98 and 99 Trafalgar Street, effectively formed the north side of the square. The 1881 Census returns show Hack aged 86, still living at 99 Trafalgar Street with his three unmarried daughters, his “income derived from property”.

Daniel Pryor Hack’s son, Daniel Hack (1834-1910) has been described as “one of the most significant Quakers of nineteenth-century Brighton.”69 This Daniel and his wife lived in the family home in Withdean, whilst his sisters Priscilla and Mary continued to live at 98-99 Trafalgar Street until the early part of the twentieth century, when the family donated the house to be used as the York Place Secondary School. Daniel Pryor Hack’s offspring were all active in good works for the town and well-known for their Quaker activities.

23. Daniel Pryor Hack, 1794-1886. Image courtesy of

Harrison, R.S., Brighton Quakers 1655-2005 (Brighton: The Religious Society of Friends Brighton Meeting, 2005), p. 26

24. Daniel Hack, 1834-1910. Image courtesy of Harrison, R.S., Brighton Quakers 1655-2005

(Brighton: The Religious Society of Friends Brighton Meeting, 2005), p. 45

The Wiber Family

At a very different place on the social scale, the Wiber family also had a long connection to Trafalgar Street. In 1841, the census enumerator listed the growing family of Charles Wiber, dyer and scourer, where he and his wife Elizabeth had nine children including three-year old triplets, his handwritten addition to the record saying “Note! All at one birth”.

25. Wiber family census page, 1841. Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office

The Wiber triplets, Edward, Eliza and Margaret, are extraordinary in that infant mortality during the Victorian era was high, sometimes as much as 50%, and these three not only survived their early childhood but can be traced through the Census until the 1880s when they were in their forties.

The numbering in Trafalgar Street varies in the 1840s, but it seems as if the Wiber family lived in the same house, which became number 104, for over twenty years. Then, between 1867 and 1870, Charles and Elizabeth moved with these three unmarried offspring, aged 32, to number 4; with the son working as a dyer like his father. Ten years later Charles was a widower, his two daughters still unmarried, living at home, and working as dyer’s assistants. The son Edward had married and was continuing to work as a dyer, living at Mighhell Street.

By 1891, the Wiber triplets seem to have all died, or at least cannot be traced through Census records. Edward’s only surviving son could be found living with his mother in Warleigh Road, Preston; she had remarried a railway porter, who was working as a printer and compositor.

Life and work

Sanitary Conditions

In spite of being famous for the sea water cure, the over-crowded working class streets of Brighton were breeding grounds for cholera, typhoid, consumption, and smallpox. Few families could afford doctors and Dr. William Kebbell said in 1848, “In no town in the kingdom do the extremes of cleanliness and squalor exist more than in Brighton”.70 The social mix in Trafalgar Street suggests that this cleanliness and squalor were indeed next door neighbours, and it is not surprising that Daniel Hack and Thomas Carter wished that their houses should face a tranquil square with large gardens to the rear.

From Brighton Borough Council byelaws, we can deduce what kind of conditions prevailed and needed to be regulated. In 1865 and 1874 building byelaws were drawn up to decree the level, width and sewerage of new streets and the construction, ventilation and drainage of buildings. Rubbish and refuse were a problem, so that in 1874 regulations were introduced to prevent nuisances arising from snow, filth, dust, ashes and rubbish and the keeping of animals, as well as the cleansing of footways and pavements and the removal of refuse. Six years later there were regulations to prevent and suppress nuisances caused by the driving of certain cattle, sheep and pigs through the streets of the Borough during certain hours and without proper control.71 Clearly not everyone abided by these regulations, as in 1878 the Corporation’s Sanitary Committee served notices on the occupiers of the Railway Cab Tunnel “to remove all filth and cleanse.”72

The Cresy Report

In 1849 a health inspection and report were commissioned by the town’s ratepayers, and the resulting report by chief inspector Edward Cresy made the following damning indictment of many of the town’s worst areas, with Trafalgar Street named among them:

“The causes of sickness may be traced in the quantity of sulphureted hydrogen, which arises from the excrementitious matters retained in the several cesspools throughout the town. This deadly poison pervades all the narrow breathing-places which are found at the backs of continued rows of buildings, and where there are windows so situated as to admit it into the overcrowded apartments … Many of the houses are wretchedly damp, being constructed with inferior bricks, and mortar made of sea sand. No methods are adopted for getting rid of even the pluvial waters, and the walls are covered with lichens; so that, added to the want of drainage, a constant decomposition of vegetable matter is going on.”73

While the causes of disease were not fully understood at this time, Cresy was correct to identify cesspools and insufficient sewerage as a danger. Diseases like typhoid, cholera, scarlet fever and consumption were common.

Cresy also made particular and negative reference to the town’s slaughterhouses, and the “almost universal” practices of throwing offal into cesspools, and of feeding pigs on other animal remains before themselves being sold for food.74 In 1848 Brighton had 54 slaughter houses, including one at 16 Trafalgar Street, accessed from the alleyway now developed as Trafalgar Mews. The street was also used to herd cattle from the station to one of the biggest abattoirs in Brighton, which was situated in Oxford Court between Oxford Street and Oxford Place.

Cresy’s recommendations included the building of in-house WCs, proper sewers, removal of all cesspools, the elimination of slaughter-houses in favour of one large centre out of town, similar measures for a new cemetery, proper road paving, a public bathing-place for the poor, and engines to lift sewer water to a storage area prior to sale to agriculturalists for fertiliser.

Not all of these were implemented, but in 1882 Dr Richardson’s report on his Sanitary Inspection of Brighton noted the town’s generally good health, as seen at key institutions such as schools, hospitals, and workhouses. The water supply was regarded as “excellent.” He did remark that slaughter-houses and urban cow-sheds remained generally bad, dark, and unclean, and repeated Cresy’s call for a single regulated and inspected public abattoir.75 Some regulation did occur that same year, and in June 1894 all North Laine abattoirs finally closed, the slaughter process being transferred to the Brighton Municipal Abattoir in Hollingdean.

Of the 14 Trafalgar Street deaths recorded by the Coroner between 1902-1936, eight were from natural causes like pneumonia and heart disease, one was a child shortly after birth, another an accidental death following a fall from a window, and there were four suicides: Annie Luper fell intentionally from a window in 1919, Annie Davis drowned near the Black Rock Groyne in 1931, Wilfred Bernard gassed himself in 1933 and Samuel Frank took poison at the Unique Garage in 1936. James Durtnell, a retired butler aged 85 was recorded as an accidental death at Brighton Infirmary after being knocked down by children playing in Trafalgar Street in 1933.76

Mobility & Employment

Census returns give us interesting information about the growth and development of the town. Looking at Trafalgar Street, we can see that in 1851 there were 115 people described as head of household, of whom 16 were born in Brighton, 43 came from elsewhere in the county, 2 did not specify their place of birth, and 54 come from outside Sussex, including 3 from Scotland, 9 from Yorkshire, 1 from Lancashire, 1 from Durham, 2 from Cornwall, and 10 from Middlesex. We can imagine that Trafalgar Street had voices and accents from all over the country.

The new railway offered employment possibilities both to Sussex people and from elsewhere; and on Trafalgar Street we find not only the stationmaster, but also a switchman for Brighton Railway, a railway policeman, and an engine driver, all Sussex born, as well as railway engine fitters from Scotland and Bradord. Number 68, next to the station, housed the station master William Balchin, his wife and small son, plus 16 other people including a railway guard who was a visitor, a railway equipment driver, an engine fitter as a lodger, and an engine driver.

What drew outsiders to seek work in Brighton, besides that now available on the railway? In Trafalgar Street we find that the building boom attracted a master carpenter employing 22 men and 5 boys, a surveyor and builder, 2 plumbers, a stonemason, a woodturner and a coppersmith. Three lodging-house keepers provided accommodation for local workers. Shops catering for the growing population required the work of drapers, grocers, newsagents, tobacconists, shoemakers, licensed victuallers, hairdressers, dressmakers, chemists, watchmakers, and milliners. Two blacksmiths and a coachsmith could also find local employment. People born elsewhere in Sussex came to work as butchers, bakers, market gardeners, grocers, retailers of beer, and the town carter.

By 1911, local byelaws seem to have had some effect in regulating the chronic overcrowding, with only 66 heads of household listed, compared to the 115 itemised in 1851. Of these, 21 were Brighton born, 17 came from elsewhere in Sussex, and 28 were originally from other parts of the country or foreign born, including one from Germany, one from Ireland and one English person born in India. Ten came from London or Middlesex.

Social Life & the Adult School

A fascinating window into late one aspect of late Victorian and Edwardian social life is found in the minute books for the Adult School, held at the Quaker Mission Room at no. 41 from 1891.77 In 1899 the school leaving age was raised to 12, and most families in Trafalgar Street could not have afforded to keep children in school beyond this age. The popularity of the Adult School reflects a thirst for knowledge among working people, with average attendance at classes in 1899 at 46 men, 23.5 women and 19.3 juniors, with 380 volumes in the library.

Although bible lessons were part of the curriculum, the school also had a more general book club, classes on music and first-aid, and in 1903 introduced a series of ten-minute ‘lecturettes’ on topics of general interest, such as ‘Sun Spots’, ‘Jupiter’, and ‘Ceylon’. In 1905, a class began for the study of social problems, which have changed little in the intervening century, as shown by titles including ‘The Unemployed Question’, ‘Betting and Gambling’, ‘Alien Immigration’, and ‘Taxation of Land Values’. The third book, covering 1910-1919, mentions visiting speakers, covering topics as diverse as “The prevention of destitution and the Poor Law”, “The National Insurance Act,” “The rise of our English towns”, and “the Great Industrial and Agrarian Revolution of the 18th Century.”

Beyond its classes, the school also had a broader involvement in the area’s social life. A regular winter programme included “Pleasant Saturday Evenings,” a Christmas “at home” and New Year breakfasts. Monthly social events typically saw 60-70 attendees, and one-off events could be much larger. One featured an evening with Frances Ridley Havergal, the popular (Anglican) hymn writer, while in March 1903 the school hosted Edwin Gilbert (secretary of the National Council of Adult School Associations, who had begun to extend the movement outside Quaker circles, with great success, in Leicestershire), drawing a ‘small’ attendance of 150-200.

The school also held an annual 3-day ‘industrial exhibition’, apparently displaying craft products made by members, which in one year received 157 entries from 79 competitors, and was visited by 150 people each evening. Educational visits were organised, to places such as the Brighton Electric Light Works and the Workhouse. The school formed a cricket club, and later a football club also, and held regular jumble sales and other fundraising events.

Summer events included the August Bank Holiday outing to Grange Farm, in Poynings. In 1911 this was referred to as “A Gipsy Day in the Country,” with covered vans leaving Trafalgar Street at 9 am, and returning at 7 pm. At the farm, sports and games such as cricket and egg and spoon races, and everyone sat down to eat the picnic lunches they had brought. Tea was provided in the barn, and “Temperance Drinks” were available for purchase.

The school’s outlook was far from parochial. Linked to the national adult-school movement via a subscription periodical called the ‘One and All’, members also enjoyed regular contact with other schools in Lewes, Croydon, and Chelmsford, and clearly had a keen interest in local, national, and global issues. They held debates on motions such as “the introduction of tramways would be beneficial to the town” (held 13th March 1900, where the vote was 13 to 4 in favour), and “Should Lord Peel’s Report be Adopted by the Government?” (in March 1901).

Regular resolutions were sent by telegram to those in positions of influence, such as one to the Prime Minister in January 1908 encouraging his temperance legislation, specifically urging that pubs be closed on Sundays, have earlier closing on working days, and children be denied access to liquor. In May 1909 they urged the PM to protest the mismanagement and atrocities committed in the Congo Free State by the “nominally Christian rule” of Belgium. Other resolutions relate to Britain’s imposition of the opium trade on China, the potentially damaging effects on low earners of a 2-day coronation holiday in 1911, and urged a neutral, mediatory role for Britain in the ‘European Crisis’ of 1913. The school’s fund-raising was also international in scope. Although they had a Christmas grocery drive for local needy families, nominated by scholars, they also aimed to support a “native teacher” through the Friends Foreign Mission Association, the Indian Famine Fund, and to relieve non-combatant sufferers in the 1912 war in the Balkan states.

The 1914-1918 war drastically reduced both the activity and the numbers involved in the school, as working men were conscripted to fight. In November 1916, business meetings become quarterly rather than monthly, and by 1919 the final minutes had become very brief.

Education

Early Schools

The expanding population in the North Laine area required basic schooling at a time when little was available for the working class. Burn’s 1833 Brighton directory gives a summary of charity schools in the town. These include the Central National School for Boys and Girls in Church Street, with a connected Infant School in Gardener Street, and a further Branch National School in Warwick Street. There was also the Swan Downer’s Charity in Gardener Street, the Union Free School for the Education of Boys and Girls (on the ‘Lancastrian plan’ of Education) in Middle Street, and Brighton British Schools of Industry for Boys, Girls and Infants in Upper Edward Street. Although there were two day schools in Trafalgar Street listed in Kelly’s 1845 Trade Directory, these would have been fee paying, one for ladies at number 11, run by Miss Louisa Crago, and a second at number 91 run by Mrs Sarah Butcher. Trafalgar Street was teeming with children by 1861. In the Census, we have found that there were 76 individuals listed as “scholars”, although whether all of them attended a school is hard to ascertain, since 3 of this number were only two years old. There were in addition 17 babies under one year, 47 infants between the ages of one to five, 18 children aged 6 to 13 not recorded as “scholars” or working, and five young people aged 12 to 13 who were working. 13 year old Harry Gander was an errand boy, Eliza Tullett was a nursery girl, Grace Peckham aged 10 was a servant at the Battle of Trafalgar with Edward Burns, John Wells at 13 was working with his father as a baker, and 12 year old Henrietta Sayers was recorded as assistant in home at number 79.

Education Act

Forster’s Education Act of 1870 established elementary schools for children such as York Place and Pelham Street, the forerunners of what were to become council schools, and undoubtedly some children from Trafalgar Street would have attended. Subsequent legislation made school attendance compulsory for children between the ages of 5 and 10, and by 1902 local education authorities had replaced school boards. Secondary education became available and many new schools were built as a result.

In 1911, 29 children were recorded as attending school, 22 children 5-14 appear not to have been enrolled, and there were 14 infants under the age of 5. Bundock the draper at nos. 96-97 sent a 15 year old to school, and Lacy the boot dealer, Grainger the tobacconist, and Tupper a licensed victualler all sent their 14 year olds to school. However there were four other 14 year olds in Trafalgar Street who were already out to work: Ellen Sebbage was a domestic servant, Frederick Tupper a green grocer’s boy, Esther Tully a dressmaker, and Dorothy Annie Moore was working as a nursemaid at number 28. Esther’s family is not alone in numbering some children of school age as attending and some not. Two of her siblings aged 12 and 10 were at school, and two aged 8 and 6 were not. Whether this was an oversight either by Mr Tully or the census enumerator, or whether school attendance was not enforced, is unknown.

Hack Family Involvement

The Hack family, prominent residents of Trafalgar Street, were influential in the development of education in Brighton. A former headmaster of Brighton Middle Street School describes three generations of the Hack family as giving, over a long period, “zealous devotion to the cause of education”, proving “such a rich benefit to the town.”78 Daniel Hack, the elder, was honorary secretary to the committee of management (1813-1821), along with other prominent Quakers in the town. His son, Daniel Pryor Hack held the same position (1827-1835) and the grandson, another Daniel Hack, was appointed Manager (1875-1905).

In 1884, DP Hack sold land at 1 & 2 Trafalgar Court for an extension of York Place School,79 and four years later further expansion included a site for manual instruction and evening classes, as well as new offices for the cookery school and afflicted childrens centre,80 “becoming a considerable centre of education,”81 which was re-named York Place Secondary School at this time.82 In 1901, Daniel Hack was thanked by the headmaster for his subsidising of scholarships, seeing “that it was, as it still is the only means of placing secondary education within the reach of the poorest citizens of Brighton”.83 Overcrowding in the school led him, in 1906, to donate numbers 98 and 99 Trafalgar Street, along with their gardens and the Pelham Square enclosure, for further expansion of the secondary school and the pupil teachers’ centre.84 He is described in the history of Varndean as one of the outstanding benefactors of the school, and for many years the Chairman of Managers. “He not only gave two houses and gardens for the use of York Place Schools, but also presented the Girls’ School with fine pictures, a large display-case and valuable specimens known as the Hack Museum, special articles of furniture and very generous financial assistance for scholarships and prizes”.85

Inter-War Developments

Both York Place and Pelham Street schools became part of the provision for the Indian military hospital in Brighton during the First World War. York Place reverted to its educational purpose until the Girls School was relocated to Varndean in 1926, and the Boys in 1931. The York Place Elementary Schools then became the Fawcett School for Boys and the Margaret Hardy School for Girls (now Brighton College of Technology). The two houses in Trafalgar Street continued to be used for educational purposes until 1954, when No. 98 was demolished for a planned further extension of the school.

26. Number 98 TrSt, 1953. Image courtesy of the Regency Society

Trade

Today Trafalgar Street is a bustling and lively shopping area, catering for local shoppers; dedicated collectors of vintage clothing, vinyl and furniture; and students or workers searching out a cafe or a pub. Recent investment in the city has led to new developments like the Trafalgar Place complex in 1990 and the modern building designed by Mark Hills which houses Breeze and Redwood, on the corner of Pelham Street, facing Pelham Square. More evidence of twentieth century building can be found at the eastern end of the street where Domino’s and its neighbours are located. However, in the main, Trafalgar Street is still predominantly small-scale C19 industrial buildings and artisan housing, mostly opening directly to the street as described in the Pevsner Guide.

The 19th Century

A Rateable Valuation Book surviving from the early 1840s shows that the street was already fully developed, but that most buildings were only used as residential dwellings. Those that did house businesses served the practical, functional needs of a burgeoning community, such as the inns at nos. 5 and 37 and the slaughter-house at no. 16, while horses were stabled at no. 34, and no 64 contained a ‘warehouse and factory’.86

By 1845, Kelly’s Directory showed that Trafalgar Street had become a major commercial hub for all classes of people living in the vicinity. In this year, there were 44 premises listing trades and businesses: three butchers, five bakers, two tailors, two straw hat makers, a plumber, two public houses (one landlord was also a cow-keeper), a coal dealer, three schools (one for ladies and one for gentlemen boarding), two boot and shoemakers, four grocers, four greengrocers, a beer retailer, a bookbinder and stationer, two hairdressers, dining rooms, a cement manufacturer, two tobacconists, soap makers, a corn dealer, a carpenter, a chemist and druggist next door to a surgeon, a haberdasher, a draper, a Tonbridge Ware manufacturer and a dyer.

A window on the typical business premises of this time is given in the auction catalogue for sale of Mr John Pollard’s freehold properties, in September 1856. These included the “Bakehouse, Shop, & Dwelling House, being No. 79 Trafalgar Street.” The property was on a 14-year lease to a Mr Sayers, and comprised a shop (“at present divided”), parlour, enclosed yard, wash-house, and offices on the ground floor, living quarters on the first floor (three rooms) and attic (four rooms), while the actual bake-house and kitchen were in the basement.87

By the 1860s, Folthorp’s Brighton Directory recorded more specialist trades in the street, including listings for a chimney sweep, a toy dealer, a dealer in foreign wines, and a ‘carver and gilder’. Prosaic trades were still present. For over twenty years, Charles Wiber, mentioned above under ‘residents’, worked as a dyer and scourer based at no. 104, now home to Rare Kind Records. His son followed in the same business, and two daughters became his assistants. Scouring was the nineteenth century precursor to dry cleaning for fabrics and furnishings which could not be laundered. Dyers dyed silks, satins, woollens, bombazine and so on, the prevalence of the trade possibly attributable to the great need in the nineteenth century to transform garments into mourning wear. In 1870 George Taylor’s plumbing business was advertised in Page’s Directory. He lived at no. 102, and in 1868 had taken a 21-year lease on nos. 100 and 101, a substantial trading space (now Rocket Science toys and the Lucky Star restaurant) including the “coach house and stable in the rear thereof.”88

By 1897, according to Towner’s Brighton Directory, there were 72 businesses functioning in Trafalgar Street. The straw hat makers and Tonbridge Ware manufacturer had long since gone, and there is evidence that not all the shops were family-run. The Norwich Clothing Company, the London Tailoring Company, the Brighton Confectionery Company, the Preston dyeing and Cleaning Works Office all indicate changes in the retail landscape of the street, and the introduction of wholesalers and warehouses.

The 20th Century

Pike’s Directory of 1900 shows us that some now-household names already had premises in Trafalgar Street, including the Co-operative Clothing Stores, Maynards confectioners, and Freeman, Hardy & Willis, ‘boot warehouse’.

However, comparison of the 1911 Census returns with Kelly’s Directory of the same year shows that many businesses were still family run, with families living above their shops. On the south side of the street, the Duddridge family were bakers and confectioners at number 2 (now the Damage hair salon), operating from a single-storey bakehouse built in 1903 and still visible at the rear of the shop, with gated road access from St George’s Mews.89 It is easy to imagine this gateway humming with activity, both for deliveries of flour and other ingredients, and outgoing carts of bread bound for customers’ homes and businesses.

27. Duddridge the Baker, c.1903. Image courtesy of Step Back in Time, 36 Queens Road

28. Duddridge's Gateway in 2015. Image courtesy of I. Walden

Edwin Partington was a clothier at number 3 (now home to funeral directors Newman & Stringer), employing his daughter as an apprentice. Mrs Julia Gilham employed five members of her family in her newsagents’ business. Fred Ray worked on his own account as a baker, assisted by his wife and father, while Ernest Harry Bundock, the draper at nos. 96-97, was supported by family members in addition to several employees who lived on the premises.

Through the Census, we find that in many of the shops wives were assisting husbands in the business. In some cases, women’s employment also included the care of boarders, whilst Jane Bristow was the caretaker of the Society of Friends Mission Room at no. 41, and the wife of the Municipal Secondary School caretaker (Thomas Duggan) also undertook work for the Brighton Education Committee.

Although many of these hard-working families lived above the shop, in some cases the manager had the upstairs accommodation. A good example is Arthur Stacey, the ‘Assistant District Manager in Retail Meat’ living with his household above the butchers, Eastmans Ltd. at no. 28, now Raining Books.

Very few people living in Trafalgar Street in 1911 were out of work. One was an ‘unemployed spinner’ from Clackmanshire at no. 35 (now The Dining Rooms). Another was recorded as an ‘unemployed male domestic’ at no. 42, where his daughter Mrs Ellen Pacy was a confectioner and tobacconist on her own account.

A handful of the Trafalgar Street residents employed servants, mostly in public houses, such as the Dodkins’ in the Prince George, and three servants at the Prince Albert. Others include Dorothy Annie Moore, a nursemaid in the Stacey household, Ellen Sebbage in the baker’s household at number 80, and the staff of pawnbroker John Fileman, hosier Annie Stevens at no. 90, and Edward Colwell, the fish merchant.

Ten years later, Kelly’s Directory of 1921-1922 records both change and continuity. Some family businesses have survived, like Duddridge the bakers at number 2. Partington is still at number 3 as clothier and outfitter, whilst Mrs Gilham is in charge of the newsagent’s business at no. 7. Some premises have continued with the same trade, although under a different name, so a butcher, grocer, confectioner and baker are being run by new people, and public houses have new landlords and sometimes different names, but post-war Trafalgar Street remained essentially the same mix of shops and trades.

Trafalgar Mews

Throughout its history, one Trafalgar Street address of particular interest has been number 16. Originally a butchers and slaughter house, it later became a motor repair and engineering business, run by the Goldberg family who later developed a funeral business for the Jewish community, making coffins and providing transport to the Jewish burial ground at Florence Place.90

29. Number 16 Trafalgar Street, 2015. Image courtesy of I. Walden

Look carefully at the archway and you will see the butchers’ tiling. Already listed as a slaughter-house by the early 1840s, the facility was extended into the yard (now developed as Trafalgar Mews) for William Adams, the proprietor, in 1869. He built a separate WC and washing area between the house itself and the slaughter room, behind which was a two-storey bullock pen and stable, both with lofts above.91

30. Slaughterhouse expansion plans, 1869.

Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office, ref. DB/D/8/826

On 17th November 1883, Adams (or a son bearing the same name; street directories list a ‘W. Adams’ as proprietor from 1848 through to 1898) was summoned before Brighton magistrates. He was charged with assaulting Thomas Ashdown, an assistant sanitary inspector, according to the Brighton Herald, who recounted events under the headline “Savagery at the Slaughterhouse”. Adams was accused of locking the gates and then chasing Ashdown around the yard with a meat hook attached to a pole! In court, Adams frequently interrupted, made derogatory comments about Ashdown, such that the magistrate threatened to have him removed from the court. Given the choice of a fine amounting to 10 shillings and costs, or 7 days’ hard labour, Adams initially shouted that he would go to prison, but returned a minute later noisily asking for “the bill” and saying he would pay it. Much shouting later, and having been dragged by several officers to the police station, he eventually paid the fine.

In 1934 the premises saw a dramatic change of use. Purchased for £2,000 by Mr H Goldberg, a coppersmith from Poland who had moved first to London, then in 1918 to Brighton, it was transformed into a garage where he ran a motor repair and engineering business, making metal body parts for cars. He was a huge man, weighing 28 stone, who could neither read nor write English, yet he invented his own formulae for fluxes for ferrous metals.

In 1930, he began contracting to the Brighton and Hove Hebrew Congregation to carry out funerals. He and his sons made the coffins and provided transport for burials at Florence Place, Ditchling Road, which was donated to Jewry in 1826 by Thomas Kemp. He died in 1953, at the age of 70, leaving his sons to carry on the business. Both Louis and Bernie Goldberg were born with cerebral palsy, but learned to drive, kept up with computer technology, and successfully ran their business. Louis served during the Second World War as a despatch rider and mortician for the civilian dead, and in 1950, when the British Embalmers' Society was formed, he sat the examinations and gained top marks, thus becoming the first Jewish embalmer in the UK. He served as Chairman of Brighton and Hove Spastic Society (now Scope) and also of the Brighton and Hove Charitable Youth Trust. Bernie studied engineering design, and was conscripted at the age of 16 to engrave dials, controls and weapon parts for the Russian allies, and was married in 1954. Their extensive company archives are held at the Keep.92

Conclusion

This brief history of Trafalgar Street demonstrates that once you look behind the facade of the existing buildings, there is a complex and fascinating picture charting the growth and development of Brighton as a whole, from the days when the old town was surrounded by large fields, through the coming of the railway, to the present day. More research still needs to be done and if you or your family come from Trafalgar Street, you may be able to help expand the history of individual properties.

References

-

Berry, S., ‘Brighton in the Early 19th Century’ in Leslie, K. and Short, B., eds. An Historical Atlas of Sussex. Chichester: Phillimore, 1999, p. 94

-

ESRO, Property Deeds, [1821]-1833, ACC 8367/4

-

ESRO, Letters from MB Tennant to Brighton Improvement Commissioners, 1847-1849, DB/B/60/73/78

-

Collis, R., The New Encyclopaedia of Brighton. Brighton: Brighton and Hove City Council, 2010, p. 269

-

ESRO, Pamphlet of supporting information for outline planning permission for new offices for Ewbank Preece Limited, Feb 1983, ACC6746/1

-

ESRO, Brighton Borough Council Estates Department, Acquisition of the Beehive Inn, 1959-1976, DB/A/1/365

-

ESRO, Brighton Corporation (Blackman Street) Compulsory Purchase Order 1959, DB/A/1/362B

-

ESRO, Letter from Borough Surveyor, Engineer, and Planning Officer of Brighton Corporation to Tamplin’s lawyers, 11 Apr 1963, DB/A/1/365

-

ESRO, Conveyances of 86-88 Trafalgar Street and 41a Whitecross Street, Brighton, BH/G/2/3804

-

ESRO, File of documents related to Compulsory Purchase of buildings in Trafalgar Street, 1969-1977, R/A/6/52

-

ESRO, File of documents related to Compulsory Purchase of 96-97 Trafalgar Street and 1-2 Pelham Street, 1972-1977, R/A/6/53/56

-

ESRO, Pamphlet of supporting information for outline planning permission for new offices for Ewbank Preece Limited, Feb 1983, ACC6746/1

-

ESRO, ESCC Traffic Orders R/C/47/20/177, R/C/47/21/14, R/C/47/22/154, and R/C/47/22/266.

-

Antram, N. & Morrice, R., Pevsner Architectural Guides: Brighton & Hove. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2008, p.88

-

ESRO, Deeds of 98 and 99 Trafalgar Street, including plans for the proposed Pelham Square development, R/C/4/461

-

Collis, R., The New Encyclopaedia of Brighton. Brighton: Brighton and Hove City Council, 2010, p. 269

-

ESRO, Alteration Plans for 96-97 Trafalgar Street and 1-2 Pelham Street, 1902, DB/D/8/4943

-

ESRO, Alteration Plans for 102 Trafalgar Street, 1867, DB/D/8/550

-

ESRO, Alteration Plans for 100-101 Trafalgar Street, 1869, DB/D/8/828

-

ESRO, Alteration Plans for the Great Eastern, 103 Trafalgar Street, 1895, DB/D/8/4095

-

ESRO, Alteration Plans for 104 Trafalgar Street, 1868, DB/D/8/743

-

ESRO, Papers of Revd John Nicholl, vicar of Westham, 1703-1770, AMS 5755

-

ESRO, Property Deeds, [1821]-1833, ACC 8367/4

-

ESRO, Deeds of 25 Trafalgar Street, [1823]-1852, WEB/ACC2608/1/15. Deeds of 32-33 Trafalgar Street, 1833-1869, DMH/ACC8745/75/1. Conveyance of 35 (then 38) Trafalgar Street, 1848, ACC 9926/1.

-

ESRO, Deeds of 31 Trafalgar Street (formerly 34), 1824-1882, DMH/ACC8745/75/2. Conveyance of 35 Trafalgar Street (formerly 38 Trafalgar Street), 11 Aug 1852, ACC 9926/2 and Deeds of 35 Trafalgar Street, ACC 9129.

-

ESRO, Deeds of Council Property: The Beehive Inn, 1830-1988, R/C/4/81

-

ESRO, Deeds of Council Property: 91 Trafalgar Street, 1880-1962, R/C/4/213

-

ESRO, File of documents related to Compulsory Purchase of buildings in Trafalgar Street, 1969-1977, R/A/6/52

-

ESRO, List of Drainage (i.e. street sewers) Plans, #30, DB/D/6/10. This index directs archive users to plans held under series DB/D/17, but these plans use a different numbering system from the index, and it is uncertain whether they are the plans referred to. Staff at the Keep are currently investigating (September 2015).

-

ESRO, Minutes of Brighton Borough Council Works Committee, 1856-1858, DB/B/16/1

-

ESRO, Plans of Lamps, DB/D/6/13

-

ESRO, Minutes of Brighton Borough Council gas, lighting and electricity committees, 1877-1884, R/C/16/1

-

ESRO, Plans of gas mains in Trafalgar Street, 1885, DB/D/46/335 (held as DB/D/39)

-

Collis, R., The New Encyclopaedia of Brighton. Brighton: Brighton and Hove City Council, 2010, p. 269. Inspection of Street Directories indicates that the words ‘and cowkeeper’ are a secondary occupation of the inn’s proprietors, rather than part of the inn’s name.

-

ESRO, Scrapbook containing photographs, cuttings and ephemera relating to pubs, shops and other businesses in locations including Trafalgar Street, BH600894

-

ESRO, Minutes of Brighton Borough Council Works Committee, 1856-1858, DB/B/16/1

-

ESRO, Leases of Ship Street Brewery public houses by Henry Willett to Charles Catt, 1872-1874, FHG/ACC3402/1/2/7

-

ESRO, Conveyances of the Willett Estate, 1895, AMS7066/1

-

ESRO, Register of Licences, 1900-1922, PTS/2/6/6

-

ESRO, Licensing Plans: Prince George, 5 Trafalgar Street, 1933, PTS/2/9/522

-

ESRO, Scrapbook containing photographs, cuttings and ephemera relating to pubs, shops and other businesses in locations including Trafalgar Street, BH600894

-

ESRO, Scrapbook containing photographs, cuttings and ephemera relating to pubs, shops and other businesses in locations including Trafalgar Street, BH600894

-

ESRO, Handbill advertising a meeting at the Lord Nelson pub, Trafalgar Street, Brighton, AMS6848/3/5/1

-

ESRO, Scrapbook containing photographs, cuttings and ephemera relating to pubs, shops and other businesses in locations including Trafalgar Street, BH600894

-

ESRO, Register of Licences, 1885-1900, PTS/2/6/5

-

ESRO, Tamplins Brewery Property Register, 1896-1966, TAM/1/29/1

-

ESRO, Scrapbook containing photographs, cuttings and ephemera relating to pubs, shops and other businesses in locations including Trafalgar Street, BH600894

-

ESRO, Register of Licences, 1900-1922, PTS/2/6/6

-

ESRO, Tamplins Brewery Property Register, 1896-1966, TAM/1/29/1

-

ESRO, Scrapbook containing photographs, cuttings and ephemera relating to pubs, shops and other businesses in locations including Trafalgar Street, BH600894

-

ESRO, Alteration Plans: Prince Albert Hotel, 1881, DB/D/8/2122

-

ESRO, Scrapbook containing photographs, cuttings and ephemera relating to pubs, shops and other businesses in locations including Trafalgar Street, BH600894

-

Brand, M., ‘Peggy the Dog’ [Online], North Laine Community Association, http://www.nlcaonline.org.uk/page_id__123_path__0p5p42p.aspx [Accessed 11/11/2015]

-

ESRO: Alteration Plans: Trafalgar House, 1864, DB/D/8/356

-

ESRO, Register of Licences, 1885-1900, PTS/2/6/5

-

ESRO, New Building Plans: Holly Bush Pub, Frederick Place, 1892, DB/D/7/2883 (also on microfiche under reference DB/D/134/2883)

-

ESRO, Scrapbook containing photographs, cuttings and ephemera relating to pubs, shops and other businesses in locations including Trafalgar Street, BH600894

-

ESRO, Register of Licences, 1885-1900, PTS/2/6/5

-

ESRO, Register of Licences, 1885-1900, PTS/2/6/5

-

ESRO, Scrapbook containing photographs, cuttings and ephemera relating to pubs, shops and other businesses in locations including Trafalgar Street, BH600894

-

ESRO, Tamplins Brewery Property Register, 1896-1966, TAM/1/29/1

-

ESRO, Society of Friends: Letter from the Sussex, Surrey and Hampshire Quarterly Meeting, concerning the division of the proceeds of the sale of 41 Trafalgar Street, 6 Mar 1945, ACC 9265/1/8/1

-

Ibid.

-

Harrison, R.S., Brighton Quakers 1655-2005. Brighton: The Religious Society of Friends Brighton Meeting, 2005, p.39

-

ESRO, New Building Plans: Garage in Trafalgar Street, 1924, DB/D/7/6751

-

Roberts, M. ‘Brighton and Hove’ [Online], National Anglo-Jewish Heritage Trail, http://www.jtrails.org.uk/trails/brighton-and-hove/places-of-interest [Accessed 11/11/2015]

-

Antram, N. & Morrice, R., Pevsner Architectural Guides: Brighton & Hove. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2008, p. 62

-

Harrison, R.S., Brighton Quakers 1655-2005. Brighton: The Religious Society of Friends Brighton Meeting, 2005, p. 15

-

Ibid., p. 44

-

Royal Pavilion, Museums & Libraries, ‘Exploring Brighton Gallery’ [Online], http://brightonmuseums.org.uk/discover/2015/02/26/exploring-brighton-gal... [Accessed 11/11/2015]

-

ESRO, Brighton Borough Council byelaws and regulations, 1875-1907, DB/D/72/2

-

ESRO, Brighton Sanitary Committee Minutes, 1876-1881, R/C/11/1/1

-

ESRO, Report on Sewerage etc., by Edward Cresy, 1849, BH600154, page 10

-

ESRO, Report on Sewerage etc., by Edward Cresy, 1849, BH600154, page 25

-

ESRO, Bound Volume of pamphlets on Sanitation, BHVol14

-

ESRO, Records of the Coroner for Eastern Sussex 1817-2003, COR/3/2

-

ESRO, Society of Friends: Adult School (Trafalgar Street) Minutes, SOF/13/62/3/1 (1899-1903), SOF/13/62/3/2 (1903-1910), and SOF/13/62/3/3 (1910-1919)

-

Haffenden, G., The Middle Street School, Brighton, 1805-1905: A Record of One hundred Years’ Primary Instruction. Brighton: J.Beal & Son, 1905, pp.14-15

-

ESRO, Deeds of Council Property: 1-2 Trafalgar Court, R/C/4/454/454

-

ESRO, New Building Plans: Board School, Trafalgar Court, 1898, DB/D/7/4702

-

Allt, T. & Robson, B., Onward and Upward: York Place to Varndean 1884-1975. The Old Varndeanian Association, 1993, p.21

-

Carder, T., The Encyclopaedia of Brighton (Edn 3), Brighton & Hove: East Sussex County Libraries, 1990, p. 189d

-

Allt, T. & Robson, B., Onward and Upward: York Place to Varndean 1884-1975. The Old Varndeanian Association, 1993, p.44

-

Ibid., p. 48

-

Miller, J., The York Place Varndean Story 1884-1984. Brighton Print Centre, 1984, p.64

-

ESRO, Brighton Parish Valuation Book A, part 2, folios 101-202, BH/B/5/4/2

-

ESRO, Printed particulars of sale: 79 Trafalgar Street, 1856, ACC4299/5/95

-

ESRO, Counterpart lease of 100 and 101 Trafalgar Street, 1917, ACC 7774/2

-

ESRO, Alteration Plans: 2 Trafalgar Street, 1903, DB/D/8/5081

-

Collis, R., The New Encyclopaedia of Brighton. Brighton: Brighton and Hove City Council, 2010, p. 269

-

ESRO, Alteration Plans, 15 Trafalgar Street, 1869, DB/D/8/826

-

Abrahams, L. ‘They bore no grudge at fate’ [Online], North Laine Community Association, 2011, http://www.nlcaonline.org.uk/page_id__813_path__0p5p42p.aspx [Accessed 11/11/2015]