Street history - Foundry Street

Lead researchers: various MHMS volunteers

Introduction

Foundry Street is one of the many streets that constitute the North Laine. In common with many of its neighbours, it has a good mixture of residential and commercial properties that, through the years, have included shops, pubs, factories, warehouses and offices. Additionally, it is of historical importance due to its proximity to the Regent Foundry – formerly, one of Brighton's largest industrial employers and the seat of the first electricity production in the town in 1882. This combination of mixed usage and its central location within the North Laine makes Foundry Street typical of the area and an interesting street to study.

Exploration of Foundry Street’s history helps overcome the tendency to consider the streetscape at eye level and encourages investigation of the upper parts of the properties. Here, there is much evidence of the street’s former industrial use. For example, in the large upper windows and the remains of hoists and pulleys that were once used to raise goods up to the second or third floors of the large buildings originally built as warehouses. These have now often been converted to provide modern city living spaces. Combining the discoveries we have made by investigating the buildings themselves with information gathered from documents has enabled the production of a detailed street history.

The story of Foundry Street’s development is inseparable from that of The Regent Iron and Brass Foundry. This business seems to have originally evolved in Regent’s Street, close to the Royal Pavilion but to have relocated in about 1823(1). It moved to occupy land to the west side of today’s Foundry Street and almost immediately had its name associated with the developing street. Earlier the pathway that ran along its eastern side provided a route for market gardeners to access their plots.

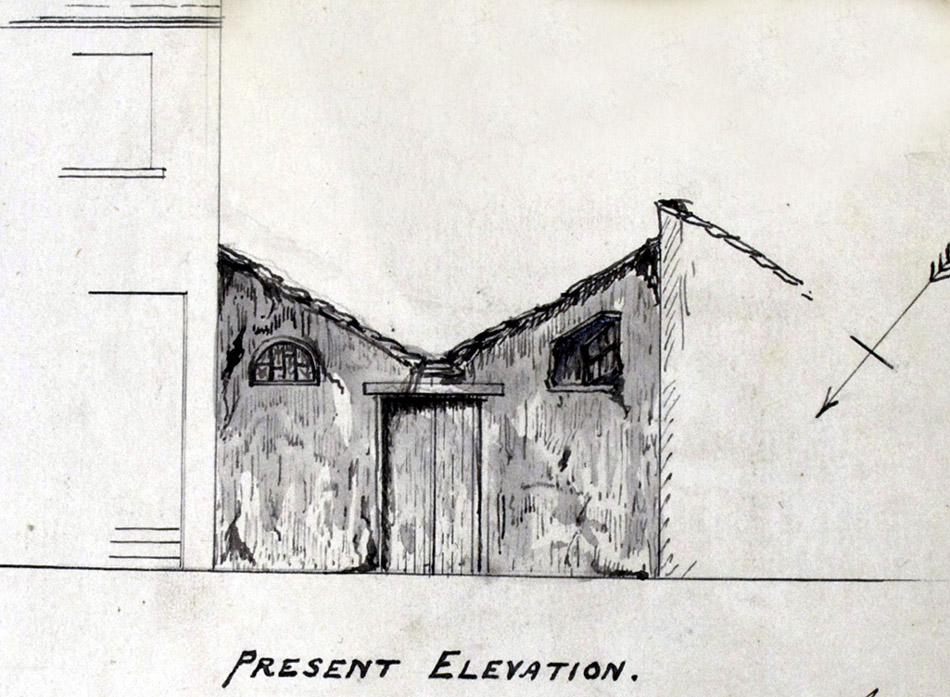

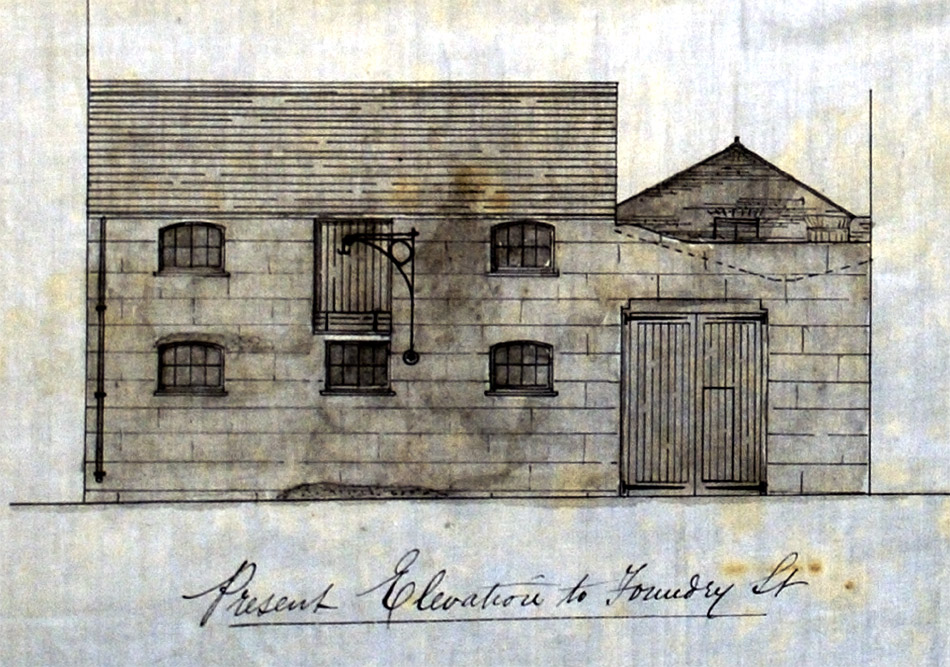

The Foundry represented a major centre of production and it seems that small business workshops were quick to spring up along its eastern side thereby starting the development of the road proper; as tradesmen took advantage of the commercial opportunity to supply goods and services that were often, but not necessarily, allied to or associated with the Foundry’s primary business. As the street gradually developed, it appears that these basic artisan’s workshops were slowly replaced in an ad hoc manner by warehouses, formal workshops and residential tenements, where and when the space became available. Figure 1, provides an insight into the first buildings to appear in the street, this particular example was demolished in order to build a substantial two-story coach maker’s workshop (now known as number 9).

As Foundry Street took on its now familiar structure, it acquired more permanent residents. These individuals become traceable through records such as census returns, trade, and street directories.

This document considers first the Regent Foundry and then moves on to provide details about the houses, the people and the institutions that formed the Foundry Street of the past.

1) Sketch of a workshop in Foundry Street, June 1868. Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office

The Regent Iron and Brass Foundry

The Regent Iron and Brass Foundry was the largest in Brighton and as such, a major employer in the town. The ‘Pigot & Co Directory 1840’ for Sussex states that:

"There are several iron and brass foundries – one of these (the Regent Foundry), belonging to Messrs. Palmer, Green and Co., is upon a very extensive scale, and well worth inspection" (2). It seems that visiting places of workand industry, such as the foundry, was a popular pursuit in the late-Georgian period. For example, in 1824 Elizabeth Sandham wrote a book entitled "A visit to the Regent Iron and Brass Foundery, the Gas Manufactory, and the Royal Chain Pier" (3). In this didactic work written for children, Sandham visits the three venues, ostensibly with two children acting as her interlocutors asking questions and talking about what happens at the foundry, the gas plant and how the Chain Pier was constructed.

The Chain Pier was Brighton's first pier and opened in 1823. Much of the ironwork for the pier was cast at the Regent Foundry, although the chains themselves were wrought and obtained from Wales. The foundry also cast ‘Retorts’, which were ovens used for burning coke (processed coal) in the town’s gas production plants.

A foreman at the foundry describes the site to visitors, as being in its "infancy at present", though he hoped it would grow. In 1823 the foundry employed “not more than 50 men” and the technology in use at that time appears to have been limited; it is stated in the book that they intended to get a steam engine to work the bellows, as man-power was used initially.(4)

Casting work undertaken at the foundry was a skilled process that involved many craftsmen of differing trades, not just metal workers. This is because the production of cast objects relies upon carved wooden ‘bucks’ or master moulds made by carpenters, joiners and carvers and is described in the following extract:

"Cast iron was formed into structural elements by pouring the molten and extremely fluid material into moulds formed in damp sand. These moulds were normally in two halves which were brought together initially against a timber 'pattern' that left an impression in the sand of the desired shape of the iron component. The two halves of the mould were separated, the timber pattern removed and the mould re-assembled ready to receive the molten iron. When the metal had cooled and solidified, the sand was simply brushed away and then used again to form another mould. This meant that each individual cast iron element was specially made and that the shape could be as complex as the two-part sand mould would allow." (5)

It has yet to be ascertained whether Messrs. Palmer, Green and Co. actually owned the foundry or leased it and we await the discovery of documents that might resolve this issue. However, it is clear that the foundry was successful and expanded under their management, becoming at one point the largest employer in the town.

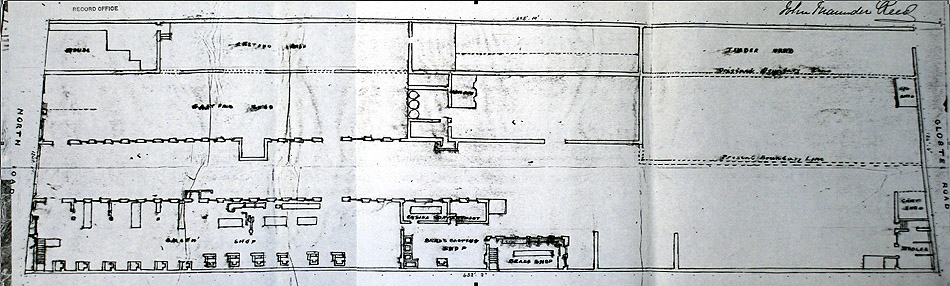

In 1870, a 21 year lease between the then owner, James Martin of Brighton (Gentleman) and lessees Charles German Reed & John Maunder Reed also of Brighton (Ironmongers) was drafted. This is dated 25th March and at a rate of £320 per annum it provides for two ‘counting houses’ (we would call them offices today), together with three casting shops, separate smith and brass shops, a polishing department with a separate steam engine, a coke oven and a large timber yard and sawmill at the Gloucester Road end. There were also two ‘Register stoves’, eleven forge beds and chimneys, a ‘shed for trucks’ (a gig shed) and three stall stables. Much of this detail is captured on a plan of the foundry that is attached to the aforementioned leasehold indenture (plan reproduced below as figure 2).

2) Plan of the Regent Iron and Brass Foundry, 1870. Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office. Enlarge

Many manufacturers based in the North Laine showcased their produce in department stores in nearby North Street and by 1902, the Sussex Daily News could report that, ‘Everybody in Brighton knows Messrs C G Reed and Company Ltd’s commodious show rooms at 26 North Street’. By the turn of the century, the firm was producing countless household items for sale at home and abroad, exporting not only to Europe but also to India, China, Japan and South America.

The range of goods on offer included: brass fire irons, fenders, curbs, firedogs, irons, coal scuttles, vases, fire screens, table kettles, music stands, paper racks, jardiniers (sic), letter racks, sconces, candlesticks, candelabra, lamps, wall brackets, stoves and fire grates to name but a few! It would be fascinating to discover how many examples of these wares survive in Brighton homes today.

As well as producing items destined for domestic use, the Foundry was also well regarded for its commercial products that included agricultural implements and brewers’ appliances. It was also capable of large-scale industrial casting for major clients such as the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway Company and local civic authorities. The Sussex Daily News listed a number of civic examples produced in the foundry that could be observed in situ and that, in its opinion, contributed to the aesthetic appeal of Brighton’s urban development. These included its, ‘handsome electric light standards, the substantial and well designed railings of the three mile of Brighton front, the railings of Preston Park, Queen’s Park and the Level, in street channel tanks, cellar coverings and many other respects’. Of course, some of these works have been lost to us due to wartime propaganda (encouraging the donation of iron to the war effort) and changing fashions.

Strolling along Foundry Street today one would be hard-pressed to imagine that this calm city thoroughfare, with its sought-after houses, central pub and office space was, less than 150 years ago, at the centre of Brighton’s industrial heartland. It is also remarkable to think that the foundry’s early electricity generator began to be used as a public supply by the town as early as January 1882, and that, as we have since enjoyed an uninterrupted service, “Brighton can probably claim the oldest continuous electricity supply in the world".(6) All of this from Foundry Street!

The Development of Foundry Street

It has been suggested that the houses in Foundry Street were built between 1842 –7. However, it seems likely that initial development was earlier than this because the street is listed in the 1841 census and many residents names are recorded. Unfortunately, due to then common practice, no house numbers are allocated to the resident’s names entered in the census records of that year, making the 1841 census somewhat frustrating to work with.

Foundry Street developed in a piecemeal fashion, over time, as a mixture of residential and commercial premises. The east side remained largely residential, once established, but the west side of the street appears to have become predominantly industrial and commercial during the mid-to-late 19th.

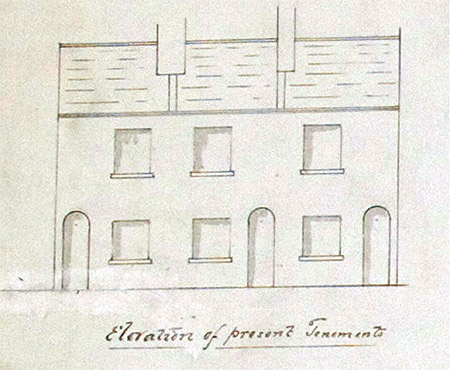

The gradual development and commercialization of the street during the 19th century is exemplified by Mr. G M Lockyer, an enterprising builder and developer who kept a stock yard on the western side of Foundry Street, next to the pub at the Gloucester Road end. Lockyer owned a large part of the western side of the Street and by 1888 he was keen to redevelop the tenements next to his yard. He submitted a proposal to the local authority in December that year to demolish numbers 28,29 and 30 and to erect a store in their place. It is unclear as to whether his application proceeded at that time. However, he certainly submitted a further proposal the following year to demolish numbers 31,32 & 33 and to erect a store there too. This was agreed and two buildings to his designs still stand today as numbers 34 and 35. See Figs 3 and 4 below for extracts from the 1880s submissions for these structures, illustrating both the tenements lost and the planned new buildings.

3) Tenements to be lost in Lockyer’s Foundry Street redevelopment. Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office

4) Lockyer’s new store buildings c.1890, Foundry Street. Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office

Overall, there seems to have been no hard and fast rules about using land for one purpose or the other and there is evidence of shops, warehouses and workshops on the east side (at numbers 3, 8 & 9), and houses on the west at numbers 25 & 26.

It might be assumed that the houses in Foundry Street were built with the intention of housing foundry workers. However, the evidence in census returns from the mid-19th century onwards suggests that this may not have wholly been the case. There are indeed smiths and iron labourers among the occupations listed in the returns, but there are also shoemakers, porters, laundry workers, carpenters and bricklayers’ labourers amongst the range of workers listed as residents.

It is worth remembering that the entered occupation of 'carpenter' on the census returns had wider scope and was used more generically than it is today and could encompass people involved in building work, including roofing and structural work, through to pattern makers, furniture makers and joiners. Carpenters therefore, may have been foundry workers, as their skills certainly would have been called for in the manufacture of the master ‘bucks’, or patterns, used in the casting process. Overall, however, there is good evidence of people with many and diverse trades living in the street.

The web site http://privatewww.essex.ac.uk/~matthew/work/occlass.htm looks at some of the problems facing census enumerators and the classification of trades within early census documentation. The Regency Town House archives contain various examples of the work that the different types of carpenters produced throughout this period.

Commercial Activity

From the examination of sources such as the Census returns for the period 1841-1901 and street directories from 1856 to 1973, a picture starts to emerge of the many competing, varying and different activities conducted in Foundry Street. At one time or another, commercial interests have included the foundry itself, as well as a bone mill and rag warehouse at No. 28, William Smith’s Patent Lead Pipe Works and Marine Store Warehouse next door at No. 27 and the stores at Nos 33 and 34.

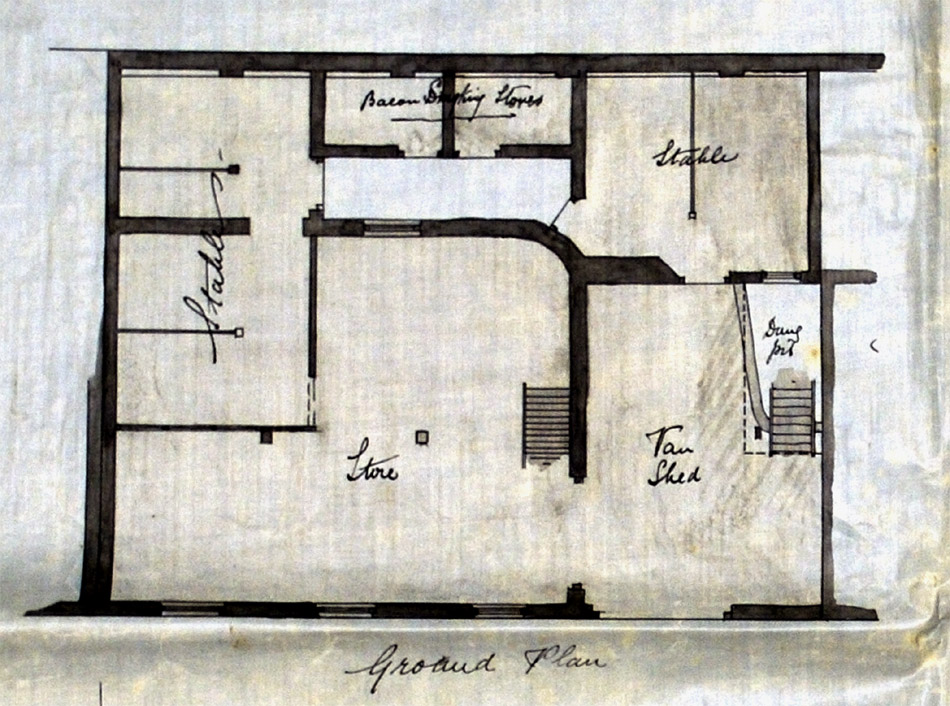

Further along at No. 35, Messrs. Walter & Lynn kept stables and a delivery van shed that also contained stoves for bacon smoking - an activity that might appear to have been run as a sideline, but was in fact central to their main business as Wholesale Grocer and Provision Merchants.

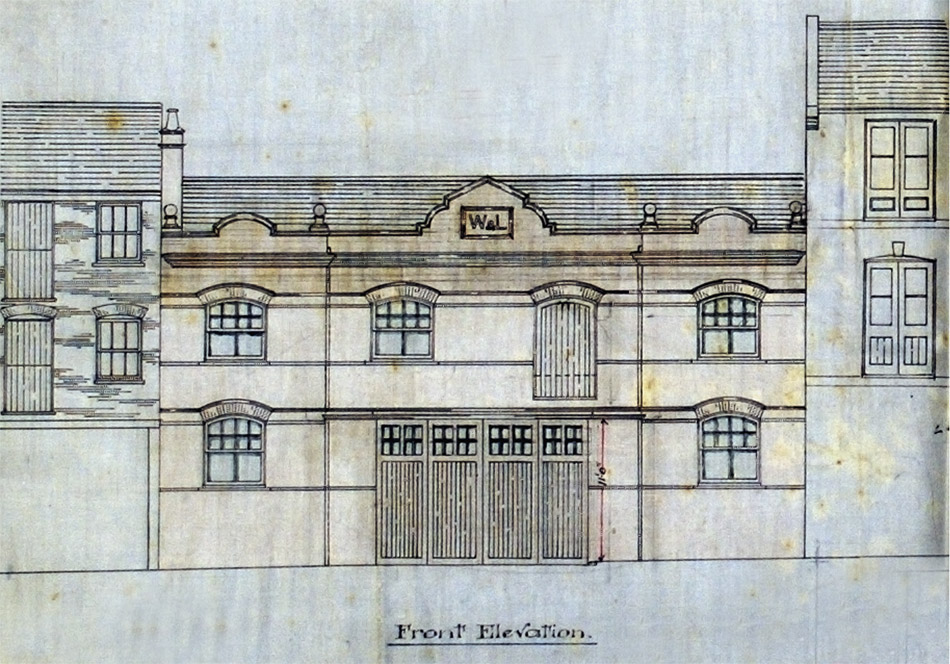

In circumstances that would make an Environmental Health Officer’s hair stand on end, these stoves were originally only a few feet away from the horses and dung (a plan and elevation of their original premises are reproduced immediately below as Figs. 5 and 6). When Walter & Lynn submitted a proposal to rebuild in 1895, the new structure (today numbered 35, 35a & 36) included a fine ornamental pediment containing the initials W&L (subsequently defaced) and, thankfully, no facilities for curing bacon – see Fig 7.

5) Plan of Walter & Lynn’s stables prior to redevelopment. Note the position of the stoves for smoking bacon – a stones throw from the dung! Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office

6) Elevation of Walter & Lynn’s stables prior to redevelopment. Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office

7) Elevation for Walter & Lynn’s new stables, as built. Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office

The street has also been host to electroplaters, scrap iron merchants, tool grinding and boring specialists, leather processing merchants, weighing machine manufacturers and van and coachbuilders. Foundry Street was not unique in this respect: we also know of a candle factory in Spring Gardens as well as soap manufacturers and tallow-melters in the immediate vicinity.

Apart from these larger commercial enterprises, there have also been many small one-man businesses operating from Foundry Street. 19th century trade and postal directories for the area list: Slater, carpenter, boot and shoe repairer, blacksmith, paper hanger, wood turner, builders, and a baker at No. 3. The bakery there was certainly active in 1848, and in 1862 it became the Cooperative Society Bread Stores run by Mr. John Griffiths. During the 20th century, the bakery developed into a grocer’s shop before being listed as a general shop and eventually ‘Maunders’. Presumably everyone knew of Maunders and no further elaboration was required!

Other small-scale, one-man, businesses active in the street during the 20th century include a tailor and a hairdresser and, a little more unusually, at Nos. 37 & 38 a rifle range - operated for a brief period between 1903 and 1904. Another exotic, and certainly longer-lived, establishment was ‘Theophilus Rex Theatrical Costumers’. This operated from No. 36 for a period of eight years from 1931 to 1939. Given its proximity to the Theatre Royal, in New Road, and the Grand Theatre, in North Road, two of Brighton’s major theatrical venues, it was perhaps ideally situated.

Health & the Slaughter Trade

It is hardly surprising, that with so much activity (none of which was particularly hygienic or silent), overcrowding and poor sanitation in Foundry Street were identified as significant problems in the 1849 ‘Report to the General Board of Health on the Town of Brighton’.

The report noted that “a collection of bones, rags and other refuse, on these premises is much complained of”. (7) This would suggest that the owners of the bone mill and rag warehouse were less than assiduous in their storage of raw materials – most of which was supplied by the plethora of slaughter houses and abattoirs that operated in the North Laine.

Geoff Mead explains that: "Animals on the hoof were walked in from Patcham and Preston and corralled on the North Steine … before ending up in the North Laine slaughter houses … By-products of these were carted up the hill to soap works in Foundry St. and tallow-chandlers in Spring Gardens".(8)

The slaughter trade was particularly unwholesome in an era of unwholesome trades; pigs were kept in open pens and fed on the blood of slaughtered animals; fat would be sold to tallow-melters for the production of candles, soap, lubricants and margarine and the residue of the carcass was cut up and sold on to the bone mill where marrow could be extracted for making glue and bones sawn or smashed up into smaller fragments to feed the mill itself which produced dust to be used as fertilizer or in the production of bone china.

An advertisement appearing in 1858 announced that ‘Bone dust of superior quality at 2s 6d per bushel may be had at Smith’s Mills’. One can only speculate what went into the production of inferior quality bone dust.

During the first part of the 18th century there was a widespread habit (not only among slaughter-men) of disposing of anything that couldn’t be sold for human consumption or industry into cesspits or down disused drinking wells. This practice contributed to the cross-contamination of wells throughout the area as the water table rose and fell and subsequently all the water in the area became polluted and undrinkable. With no fresh water on tap, the time was ripe for the proliferation of small public houses where drinkable water, usually bottled, as well as beer was available relatively cheaply.

Who lived in Foundry Street?

To assess who lived in Foundry Street we used census returns dating from 1841 (when the first modern census was taken) to the early 20th century, when the last currently accessible census was produced. The census has been taken every 10 years since 1801, but the information collected pre-1841 was on an ad hoc basis and the unsystematic approach to recording this initial material makes it of little value to street history researchers.

The first useful census (1841) shows a small number of families living in Foundry Street. We know the names and occupations of the inhabitants, along with their sex, age and whether they were born locally or in "Scotland, Ireland or foreign parts".

What the first census does not tell us, however, is which house number each household inhabited. We know how many households there are, because a double line divides them on the census enumerator’s pages, but without house numbers we are unable to confirm which individual house anyone occupied. Faced with this problem, one option is to locate the local authority rate books, which would give this information together with the name of the owner of the property (Foundry Street would have probably consisted of rented properties only at this period). However, we have been unable to examine any of the early rate books for this area (they are listed as available in The East Sussex Record Office Catalogue but are currently though to be ‘missing on transfer’).

From 1851 an identifiable pattern starts to emerge where families are established in the street and the same family names appear on consecutive census returns. From 1851, it is possible to determine where each family lived because the house number is included on the return, and we can see that some houses contain more than one household because boarders and lodgers are recorded within the household data.

With the addition of a requirement to state the individual’s place of birth on the census forms, we discover, as might be expected, that many of the inhabitants were born in the Brighton or East Sussex areas, but a number of people come from more exotic places, such as Rio de Janeiro, the USA, Gibraltar and Turkey. Additionally, there are residents who have become naturalized British citizens - a fact that was noted on the census return.

A number of extended families are listed, including a disproportionately high number of incidents of one or both spouses caring for children by a previous husband or wife – far more than is probably the case today. Whereas this is more often attributable to relationship breakdown in contemporary society, most of the carers in our study are widows or widowers. Another interesting feature is the number of families taking responsibility for the offspring of deceased relatives; an indication of the need for ‘family’ security in an era predating ‘social’ security and at a time when the magnanimity of charitable philanthropists was by no means certain.

Few of those over the age of 15 are listed as unemployed, but many of the women in particular have poorly paid jobs - often being listed as a charwoman, laundress or ironer. In an era before labour-saving devices, these jobs would have been both in demand, and very demanding.

A number of the married women are just listed as 'wife of…' and the like; others have no entry under ‘occupation’. It would appear that cooking, cleaning and running a household for a family required no effort!

It is interesting to see that even young teenagers were making a contribution to their family finances, often employed as errand boys, paper bag makers, apprentices and so on. There are also some people listed as being 'on the parish', which indicates that they were receiving a stipend from the local authority. This was money that was raised via local taxes to support the poor. There is also one man listed as a Chelsea Pensioner.

The Education Act of 1870 required the establishment of elementary schools with a responsibility to educate all children between the age of 5 and 13. The effect of this legislation is reflected in the 1871 census; almost every child between the ages of four and thirteen is listed as a scholar. Scholars are listed on previous returns, but not as frequently as in later years. However, in 1871 the enumerators appear to have become a little carried-away upon occasion, listing children as young as two and three as scholars!

Looking at census returns decade-on-decade it becomes clear that many new families were moving into the area over time and that, in some instances, emergent familial connections are forming. It seems to be a case of one person finding a job and a place to stay and then bringing in other family members. There is also evidence to indicate that people migrated to Brighton, bringing their extended family over time.

The houses of Foundry Street, though small, regularly throughout the 19th century accommodate more than one household and/or take in lodgers or boarders - the difference being that lodgers had just a bed whereas boarders had food included (bed and board). There are also incidents of tradesmen who were born outside Brighton taking in a younger person, sometimes an apprentice, from their hometown as a lodger or boarder. The 'old boys' network appears to have operated here, as others came to stay and find work.

Public transport had been developing since the late-18th century and better roads had decreased travelling time generally by the mid-19th century. The advent of the local railways in 1840 and 1841 meant that Brighton to London could be achieved in 100 minutes – just over an hour and a half - and that ordinary people had more opportunity to travel. It is perhaps this movement of people that leads to the overcrowding in some of the houses – as many as seventeen people in one property, essentially just a two-up, two-down house with two additional low-ceiling cellar rooms and an outside toilet facility, as was common to most of the houses in the immediate area.

Living across the road from an iron and brass foundry cannot have been quiet or clean. The factory used coke – processed coal – to fire the furnaces, and the street must have been full of dirt from the casting process as well as all the other local industries. In its initial stage, the foundry may have operated in daylight hours only, but it seems likely that at some point the management invested in the new-fangled gas to light the workshops in order that it could operate longer days, particularly in winter.

Public Houses & Entertainment

The Beer Act of 1830 permitted any ratepayer to open a beer house on payment of two guineas. Carder notes that, in Brighton, 100 premises were licensed in the first week and that this had increased to 424 by 1879. By 1889 there was reported to be as many as 774 public houses in Brighton - the greater portion of which were located near Brighton Station.(2) The residents of Foundry Street could take their pick from at least three pubs within shouting distance of each other: at the corner with North Road, the ‘Dolphin Inn’ (currently a music shop) offered a large space for entertainment, whilst at the Gloucester Road end a pub called, at various times, ‘The Green Man’ or ‘The Queen’s Tavern’ (now a private residence) provided a more intimate setting for its clientele. However, by far and away the most interesting and long-lived of the three is situated between its former competitors at numbers 13 and 14 Foundry Street; ‘The Pedestrian Arms’ or, as it is currently called, ‘The Foundry’.

By the mid-1800s visiting the public house had become the most popular form of leisure activity amongst working people in Brighton. Relatively cheap entertainment, pubs were meeting houses to drink, talk, sing and generally socialize with friends and neighbours, as well as offering a refuge from cold, overcrowded, damp tenements. As well as spending long periods in the pub drinking, other working class entertainments would have included cock, dog and bare knuckle fighting – often in the middle of the street. During the 1850’s local publicans began to provide entertainment for patrons with singing, dancing and comic sketches. By this time it had become popular for hot meals to be enjoyed along with the drink and entertainment. In 1860 there were 479 pubs and beer-shops in Brighton - more than all the local butchers, bakers, grocers and greengrocers combined. (9)

Walk into ‘The Foundry’ today and you step back in time; the pub has a low ceiling and a wooden floor, with a simple painted wood paneled dado. Other features that reflect the age of the pub include two fireplaces, wall mounted brass candleholders and a picture rail. In fact, everywhere you look you will see something from the past. This delightful little pub has a long history that dates back to the middle of the 19th century and there are early records of it being registered as a Beer House.

The pub’ started at No.13 and in 1856 the head of house was known to be Jacob Akehurst. At that time it was called the ‘White Horse’. Official records show that it was still called the White Horse in 1862; however by then the head of house had changed twice. This succession of landlords probably offers an explanation for the theory that the pub’s name also changed twice; first to ‘The Labour in Vain’ and subsequently, ‘The Lamb’(10) The first record that we have been able to locate (a local street directory) that refers to it as the ‘Pedestrian Arms’ is dated 1866 and lists a T. Pettett as head of house. Apart from a brief time when it became known locally as ‘The Postman’s Pub’ (because the General Post Office was situated just across the road on the site of the former Regent Iron Foundry), the name ‘Pedestrian Arms’ continued to be used until 2007, when it was changed to the ‘Foundry’. Visitors to the pub today will see that the current proprietor, Ian Coleman, has affectionately retained the old signage of the ‘Pedestrian Arms’ alongside the new ‘Foundry ‘sign.

The Pedestrian Arms remained largely within the ambit of the Pettett and Hazelgrove families and they probably have the longest record of management by two families of a single pub’ in Brighton. Certainly, Edith and Henry Hazelgrove ran the Pedestrian Arms from 1922 for over 50 years. Edith was born there in 1896 and worked behind the bar from the age of 12, when its opening hours were 5am to 11pm. She also used to play the piano in the saloon bar. The pub remained in the family for 90 years: Edith’s mother Alice Pettett took it over in 1915, after the death of her husband Thomas, and then handed it over to her new son- in-law Henry in 1922. Born in Bread Street, Henry and Edith were childhood sweethearts and they were married in St Peter’s in 1921. Henry was the son of a fisherman and he founded the Brighton Deep Sea Angling festival and the Publican’s Association Fishing Club.

References

- Elizabeth Sandham, "A visit to the Regent Iron and Brass Foundery, the Gas Manufactory, and the Royal Chain Pier", 1824, Brighton History Centre.

- Pigot & Co Directory of Sussex,1840, , Brighton History Centre.

- Elizabeth Sandham, op cit

- Elizabeth Sandham, op cit

- http://www.corusconstruction.com/en/reference/teaching_resources/archite... viewed 01/09/11.

- The Encyclopaedia of Brighton, Timothy Carder, pub. East Sussex County Libraries,1990 and http://www.mybrightonandhove.org.uk/page_id__8099_path__0p116p1360p1513p.aspx viewed 01/09/11

- Report to the General Board of Health on the Town of Brighton in 1849

- Geoff Mead, personal briefings to MHMS volunteers and various publications

- Collis, Rosie, Brighton Boozers: a History of the City’s Pub Culture, 2005, Brighton History Centre

- Collis, Rosie, personal briefings to MHMS volunteers

Further interesting reading about Foundry Street may be found at:

http://www.barbsweb.co.uk/history/ricketts.htm

http://www.barbsweb.co.uk/history/janes.htm

This is the Ricketts and Janes family website and has details of one family living in various houses in Foundry Street (numbers 29 in 1868 and 1901, 21 in 1881, 32 in 1865 and 1874) - an excellent example of domestic arrangements and extended family living in one street.