Street history - Over Street

Lead researcher Catherine Page

Download the Over Street history as a .pdf (1.6Mb)

Introduction

Over Street is in the Third Furlong of the North Laine which is located between the ‘London Road’ to the east and what was known as the ‘sheep down’ to the west (now the area above Queens Road), and between the leakways (or link ways) which became known as Trafalgar Street to the north and Gloucester Road to the south.

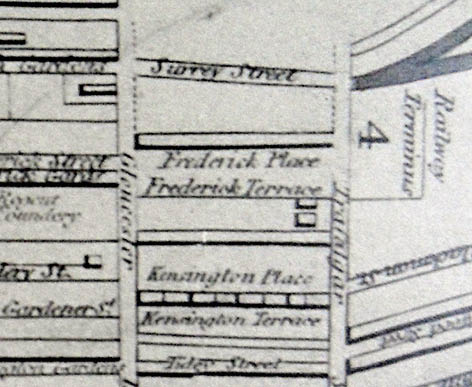

1) Terrier map of Brighton 1792 (Third Furlong here shown framed). Image courtesy of East Sussex Record Office. Enlarge

Development

In 1819, 12 pauls of land (over which 9 Over street and five adjacent houses were eventually to be built) formally belonging to the Duke of Dorset, were bought by Hugh Ross at auction. In 1841 Hugh Ross bequeathed the land to Walter William Ross. A captain in the East India Company who eventually retired to Bath, Walter Ross seems not to have known about the lands’ potential nor to have investigated it. Not only was development in the North Laine well established by then, but his pauls’ location close to the new railway terminal which provided access to the west of the country in 1840 and to London by 1841, gave it a special value. For whatever reason the land use of what was to become Over Street went unchanged through this period and thus remained largely agricultural until fairly late, by local comparison.

Eventually, in 1845 Walter Ross leased his pauls (sometimes known as paul pieces) for twenty-one years to John Parker, a schoolteacher. It seems that there was one large building on the land, called Trafalgar House, which consisted of a dwelling house, a schoolroom, dormitories, a garden, a greenhouse and stabling. The outline of what may well have been Trafalgar House can be seen on the 1842 map.

2) Detail, 1842 Reform map, Gloucester Rd - Trafalgar St,

area with possible Trafalgar House. Image courtesy of the

Royal Pavilion, Libraries and Museums, Brighton and Hove

However, Trafalgar House, under the ownership of John Parker, seems not to have been a success as a school, for in 1847 Ross, the owner of the freehold, took the remaining lease back from Parker and made an agreement with a local builder, Thomas Over. (It seems that, at the time, Thomas Over was speculatively buying land where he could, for there is evidence that he bought 6 pauls in nearby Queen’s Gardens).

In a document dated 12th April 1847 it is stated that Over should buy Trafalgar House and all its outbuildings and then erect and build “on or before the 24th June 1848... completely finished [ed] in every respect, six good and substantial messuages”1 (a messuage being a dwelling house.) Each of the houses was to be given a finished value of £200, (£200 would approximately be £11,750 today) and a ninety-nine year lease was to be granted for each building. This was the origin of Over Street, and number 9 was apparently scheduled to be one of the first built. In the meantime Over was to pay Ross a yearly rent of £100 - paid quarterly, plus a rent of £149 for the remainder of the ninety-nine years, but for seven years he was given the option to buy the properties outright for £2,800 (£163,884 in today’s money.)2

It is known that Thomas Over built number 9, but it seems that he also succeeded in building more. In a deed of 1850, number 9 is described as “abutting premises belonging to John Lewis in the north and premises belonging to Samuel Maddocks in the south.”3 One of the deeds of number 9 shows Over selling his lease on to David Horlock, another builder and in yet another deed of the same year, Horlock mortgaged the building to borrow £200 from John Duke.4

In the 1851 Census report, there are no entries for numbers 26 to 38 and this suggests that these thirteen houses had yet to be built. However, by the Census of 1861, all the chronological numbers in the street were not only built but occupied.

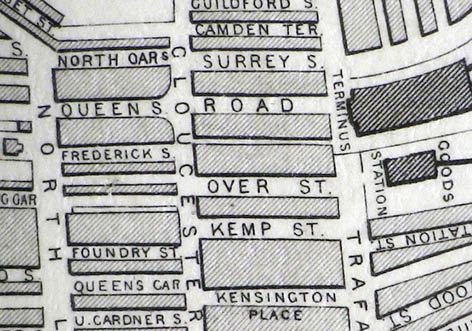

3) 1852 map with Over Street noted. Image courtesy of the

Royal Pavilion, Libraries and Museums, Brighton and Hove

As has been previously indicated, Over Street was one of the last streets to be developed in the North Laine and from the beginning it was built as residential accommodation, however a few of the residents adapted their usage from domestic to commercial interests. In the 1851 Census, there are five houses in the street which officially advertised themselves as lodging houses; these are numbers 7, 17, 24, 47 and 51. By the 1861 Census however, none of these houses were recorded as being run as lodging houses and moreover their occupants had changed. In the 1861 Census, a baker is recorded as trading from Number 17 and this eventually became a general shop and by 1871, beer was being sold from number 18. (further information on 17 and 18 can be seen in the section headed ‘Trade’ in this leaflet).

Ownership

A noticeable feature of the North Laine, and Over Street is no exception, was that landlords did not live in their own properties but leased them out to tenants, in other words a nineteenth century ‘buy to let’ scheme was the pattern for most of the houses.

A tenant might rent a single room, a couple of rooms or indeed the whole house. Two or three families occupied many of the houses at any one time, and this could involve as many as seventeen people living in very cramped and unsanitary conditions. This density of population was common throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, but it varied considerably. Some of the houses were occupied by a single family who took in just a small number of lodgers.

Whilst some houses seemed to have changed inhabitants quite regularly, in some, a single family remained in residence for a number of years and numbers 2 and 28 are examples of this. For instance, a carpenter called James Morris lived in number 2 from 1871 to 1911 while in the Census of 1871 Julia Tyrell is recorded as living in number 28. At the time she was fifty-seven and the head of the household. She had five sons living with her, aged from thirty-three years old down to fourteen, her youngest son giving his occupation as ‘errand boy’. One of her sons had brought his wife Mary Ann to live there as well and they had two daughters who worked as domestic servants as well as a six-year-old girl described in the Census as a ‘boarder’. By 1881 the family had dispersed somewhat but Julia still had one daughter and two sons living with her and another room was being rented separately. By 1891 Julia was seventy-seven and still had one unmarried daughter and two sons living with her and yet another family had moved in. By 1901, Julia was no longer there, but there was still one Tyrell in Over Street. She was called Mary and she lived at number 28.

Architecture and materials

In North Laine terms, the properties in Over Street are large, three floors above ground and often a basement. They are also late-built, being constructed during the second half of the 1840s, when many local streets had been completed and occupied for a number of years.

Despite these characteristics, the houses of Over Street are made of essentially the same set of traditional products used to build the rest of the North Laine, namely, flint and lime walling (commonly called Bungaroosh in Sussex), locally manufactured brick, Roman or early-Portland cements, lime-plasters and Baltic softwood timbers.

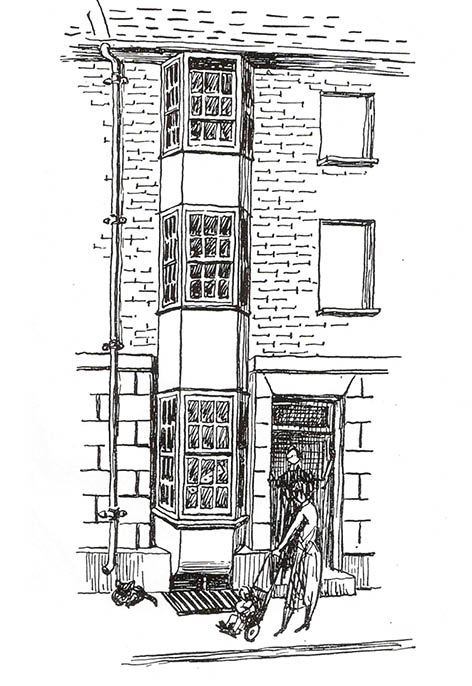

Using these materials, the designers and builders of Over Street constructed homes with rendered elevations, detailed at ground floor level with rustication (deep, wide channels laid into the render) and directly above with a stringcourse. Each home sported a three-sided bay, with double hung sashes to the central section and both side sections. The elegant, simple, geometric lines of the properties are reflected in the entranceways, each being of rectangular design and filled with a panelled door and over light.

4) Typical rusticated finish to elevations in Over Street

5) Typical three sided bay in Over Street

The properties are designed, as opposite handed pairs, so that located to the centre of each pair are the front doors. Over the doors, at first and second floor level are blind windows that straddle the party wall line.

To allow light into the basement front rooms, light wells have been inset to the pavements. These survive, albeit that a variety of cover plate solutions are now in place. The impact of financial pressures and modern materials on the finishing of individual properties is clear to see in other ways too.

Some of the properties have lost their three sided bays, these being replaced with plain vertical elevations and flush windows. Some have been re-rendered without effort being made to copy the original detailing. Metal and plastic materials, to windows and doors, are also noticeable. Despite these impacts, Over Street still strongly reflects its 19th century origins and, attests to the longevity and desirability of the Victorian terraced house form.

With a little forward planning, repairs to the street, in the future, could easily be undertaken so as to slowly reinstate much of its early character. It will be interesting to see if, over time, this is something that locals seek to achieve.

6) Sketch of Over Street by Freda Nichols, published in The

West Pier by Patrick Hamilton, 1953. Image supplied by

S. Dunsmore and reproduced courtesy of F+W Media

Amenities and alterations

The majority of houses (but not all) in the North Laine had gas lighting by 1900 (gas meters had been introduced from 1890) but a gas light was not cheap and it was usually confined to the living room. Gas gave off more light than candles but was wasteful, unreliable and dirty. It ruined books and pictures and blackened ceilings. For health reasons it was not used in bedrooms, so going upstairs in winter you needed a candle. There might also be an oil lamp in the living room, which would provide light to darn and read by.

Alice Reynolds (nee Gosden), who lived at number 11 Over Street from 1918 to 1934 with her parents and sisters, has published a book A Penny for the Gas.5 In it she provides a vivid description of what life there was like in early twentieth century;

‘There was no central heating, but as usual in schools at that time a good coal fire burned in the grate. For our protection a very large fire guard was placed in front of the fire… At home the ground floor front room was our living room and as such had a good coal fire burning. In the evenings I would sit on a chintz pouf in front of the fire, reading, or toasting bread on a long wire fork… or making ‘pictures in the fire’… However, it was very cold upstairs’.6

According to Alice, in an article published on the North Laine Community Association website, number 11 was altered little during her time there.

As many as three families could live in one house, and if this was done, the bedrooms on the first floor would be fitted with stoves. A couple might rent a room or a family two rooms. The ground floor consisted of two rooms and these were usually bedrooms, again often fitted with stoves so that tenants could cook.

The water from the range and the copper would be used to provide warm water for bathing in the kitchen. Often women were reluctant to use the tin bath and preferred to bathe in the privacy of their own rooms.

Peter Crowhurst in ‘What life was like for working class folk’ available on www.nlcaonline.org.uk further describes the sanitary conditions:

‘Water was ordinarily fetched from pipes in the street but these were often contaminated by nearby cesspits, which in bad weather leaked into them. The cesspits were bored into porous chalk often too near to drinking wells. Although Brighton had some sewers at this time, no houses in the North Laine would have been linked up to them. There were drains for rainwater, although people often used the rainwater drains to dispose of their sewage, which was then deposited on the beach.’

North Laine houses did not have inside toilets. The toilet was in a shed in the back yard where there would be no light and the only paper available was newspaper on a piece of string. During the night a piss pot underneath the bed was used.

Notable buildings

As stated above, for most of its life Over Street has been predominantly residential and thus there are no industrial buildings. Pictures of the rebuilt frontages of Numbers 17 (a general store) and 18 (a pub) can be seen in figure 7.

Residents

The Census reports provide an insight into where people were born. A study of the occupants of Over Street from 1851 to 1871 reveals that while most of its residents came from the smaller villages of Sussex, they also came from London, Yorkshire and the continent. This was a period when industry and small businesses were still establishing themselves in the North Laine and were thus attracting people from far and wide towards paid employment. Census data for 1881 on the other hand shows that more than a third of the residents of Over Street were born in Brighton and by 1901 the Census report shows that the majority of the street’s inhabitants came from Brighton. This would indicate a much more settled community and many people who lived in Over Street at the beginning of the twentieth century were second or even third generation Brightonians.

Trade

From the 1851 Census it can be gathered that many of the men who came to live in Over Street, worked for the railway company for which they undertook a wide variety of jobs. Listed in the returns are coach makers, painters, rail layers, engineers, engine fitters, clerks, general labourers, porters and guards. There were also waiters, a musician, a policeman, cooks, bricklayers, a blacksmith, tailors, boot makers, plumbers, butchers and foundry workers.

It is interesting to note that as the years went on, the number of people who lived in the street and who worked for the railway diminished, with houses for railways workers having been built in the London Road, Hanover and Five Ways. Other people took their place with more general occupations such as builders, decorators, shop assistants, carpenters, shoemakers, boot cleaners and tailors. There were also two fishermen recorded as living in Over Street, one who lived at number 13 in 1891 and one who lived at number 32 in 1911.

The women also worked in many professions, listed are: dressmakers, milliners, stay makers, shoe binders, a governess, a laundress and, of course, the ubiquitous soubriquet ‘servants’.

In the 1871 Census Report, there was a day school recorded at number 8 Over Street. There were certainly many ‘scholars’ in the street at this time, due to the 1871 Education Act, but it might be supposed that this particular school did not thrive because there is no mention of it in the 1881 Census.

In A Penny for the Gas, Alice Reynolds also talks of how her father George Gosden, a tailor by profession, had to find work in different trades due to the depression after the First World War. Clearly a resourceful man, he turned his hand to “the antiques trade, mending clocks and watches,”7 and he also made some money from refurbishing old pianos. This anecdote from Alice shows how dedicated he was to making a profit from this venture;

‘Our house had the wobbliest banister in the street, I think; Dad had sawn it in half, so that he could get pianos into the back kitchen, which he used as a workshop to repair, re-polish and tune them. When he had finished with a piano, he would advertise it in the Exchange and Mart and sell it. When the piano was out of the house, he would then fix the two ends of the wobbly banister back together again, but there was still a lot of movement’.8

7) Numbers 17 and 18 as they are today with the old shop fronts having been rebuilt. Image courtesy of Catherine Page

Like many families during the inter-war years, due to financial hardship, the Gosden family rented out a floor of their home to lodgers – after Alice’s older sisters had moved out.9

In the 1854 street directory there is mention of a grocer called Greenfield & Co at number 27. The business did not last very long because this is the only mention of it and by 1861 it had reverted to being a dwelling house. There was also a general shop at number 34, but it met the same fate as the grocery along the road at number 27.

On the other hand, as has been briefly mentioned before, numbers 17 and 18 thrived as businesses for some time, see figure 7. From the 1861 Census report we can see that William Wisden, a baker, lived at number 17. He was still trading there as a baker in 1871, but by 1881 Ann Pilbeam had taken over, listing herself as a ‘general shopkeeper’. By the time of the 1891 Census, David Legg had installed himself, at number 17, as a ‘baker and general store keeper’. A young man of eighteen, David lived above the shop with his wife and another family of four. By 1911 however, his business had prospered to such an extent that the Legg family are the only ones living there. Something then happened to David. It may well be that he was killed in the war, for by 1919 Mrs Legg was recorded in the street directory as running the shop and by 1931 her son had taken over the shop. As confirmation of its history as a bakery, the present owners of number 17 have found the chimney of the original oven.

As for number 18, it can be seen that whilst in 1861, Charles Attree had registered himself as a paperhanger, by 1871 he had become a beer retailer. Drinking water was very often hazardous to health in the nineteenth century therefore drinking beer was seen as an alternative. Number 18 thrived as a drinking establishment under the successive landlordships of Edward Artis, George Nash and Walter Richardson and eventually became a pub called ‘The Square and Compass.’ It was purchased by Tamplins and remained as a pub until the 1920s.

The street directories show the human cost of both World Wars. Until 1910, which is the last street directory to be published before the war, there were several single traders who advertised their services in these precursors to the yellow pages. As well as those at numbers 17 and 18, there were carpenters, a boot machinist, a watchmaker and a picture framer. However, by 1918 the only advertised trades in Over Street were the general store at number 17, “The Square and Compass” at number 18 and Mr Kent the plumber at number 45. There was a big gap in the production of street directories in the twenties but in the 1931 directory there was a plumber, a decorator, a tailor, a stonemason and apartments to let at number 14. By 1940, Over Street consisted of just apartments to let and the stonemason. The apartments at number 14 continued to be advertised until 1966, but after that no one in the street offered their wares or services.

Social life

Until the later half of the 20th century, most of the people living in Over Street, worked locally. They would have known each other and the shop at number 17 and the pub at number 18 would have been local gathering points.

On a more domestic level if a house was to be occupied by one large family who ate and entertained together, the front room would sometimes be used as a parlour, which was kept as the best room. It was used just on Sundays or for special guests. To have a parlour or best room indicated a certain status.

Health

8) View east over the North Laine with Over Street to the foreground left of centre. Painting: View of Brighton, from Hudson’s Mill, sketched by R. H. Nibbs, drawn by C. Childs. Image courtesy of Henry Smith Esq. Enlarge

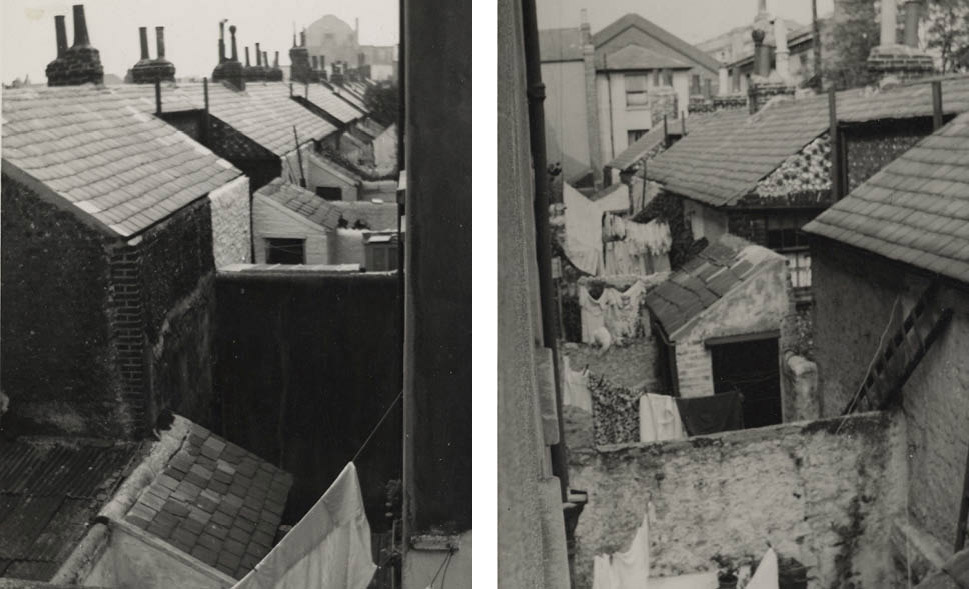

The North Laine housed many of the town’s slaughterhouses throughout the 19th century. With the arrival of the train, animals would be brought to Brighton Station and then driven down Trafalgar Street to one of the many slaughterhouses in the area. The main problem for these houses was the disposal of the waste. The universal practice was to get rid of the dung and refuse into the nearest cesspit and to give the blood to the pigs. Another source of the noxious smells was the number of farm animals kept in the area. Many of the inhabitants were former farmhands, who had been forced out of the countryside by the Acts of Enclosure of the 19th century. These people brought with them into the town the animals they had kept in the country, so in some of the backyards there were chickens and pigs.

It was important in Victorian society to be in a street where ‘decent’ people resided, and in which people kept themselves and their houses as clean as possible. It was better to be in an almost entirely residential street like Over Street where there was less likelihood of dirt from industrial premises or smells from animals as described above, and the rents would have reflected this. Another advantage of Over Street was that it was built above the industry of the lower North Laine so its water supply was perhaps less tainted by septic fluids.

Despite its elevated position, living in the area exposed its inhabitants to most of the country’s diseases. In the nineteenth century there were frequent epidemics of whooping cough, smallpox, scarlet fever and consumption. In his report in 1848 (when Over Street was being developed) Dr William Kebbell found that 5% of the population of the North Laine suffered from contagious diseases. The reason for this was the general condition of the houses and the warren of narrow streets and courtyards. The houses were poorly ventilated, badly drained and grossly overcrowded. Rubbish was left on the street, and gutters were not repaired. The sewage was deposited into open cesspits and emptied at night by scavengers employed by the council. As has previously been described, the houses were often built with inferior brick and the mortar was often made from sea sand. The walls were therefore green and covered with lichen during damp periods of the year.

Events

In the 1960s there was a proposed scheme to widen Gloucester Road. This involved the Corporation (Brighton and Hove Borough Council) purchasing houses across the North Laine, including some in Over Street. Number 48 Over Street was one such property. Intending to let it for a few years until it was demolished, the Corporation purchased the property in 1948. However, the Medical Officer of Health described it as being “totally unfit for human habitation in its present condition” so the Housing Department rejected it. The council was limited to spending no more that £1,000 to make the house good so they could not afford to make it fit for habitation. The building was therefore left derelict and when water started coming through to number 47 the owner of course complained.

What happened in the end? It can be assumed the Council made good the leak and when it was obvious the scheme was not going to happen, the house was sold at auction – as so many were.

9) Back yards in Over Street, taken by the Brighton Borough Surveyor. Image courtesy of the Royal Pavilion, Libraries and

Museums, Brighton and Hove. Enlarge

Conclusion

Over Street has remained a largely residential street with a strong identity of its own, reinforced by a vibrant annual street party.

Although many of the properties have been modernised the street retains interesting and important early building fabric attesting to past history and property use, such as the bakers shop remnants noted to be present at No. 17.

It continues to be a core part of the North Laine Conservation area and is a location with which people often form an enthusiastic and life-long attachment, as Alice Reynold’s recollections testify.

References

- ESRO, 9 Over Street, Brighton, ACC8745/52

- ibid

- ibid

- ibid

- Reynolds, A., (2008) A Penny for the Gas on http://www.nlcaonline.org.uk/page_id__548_path__0p17p193p202p.aspx [Accessed 1st September 2011]

- Reynolds, A., (2009), Growing up in the Twenties on http://www.nlcaonline.org.uk/page_id__618_path__0p18p95p36p.aspx [Accessed 4th July 2011]

- Reynolds, (2008)

- Reynolds, (2008)

- Reynolds, (2011)